Electric Poverty: Is there Life without Alternating Current?

September 6, 2002

By Gar Smith

TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO: The author experiences"fuel poverty" in the Caribbean. Credit: C. Mahabir / The-Edge |

When we encounter pictures of children trudging down unpaved roads in Guatemala, Indonesia or Nigeria without even so much as an iPod to entertain them, we are likely to recoil at such examples of Third World poverty. In the US, where our all-electric media bombard us with endless anthems in praise of wealth, riches and consumption, one seldom hears a good word for the simple life.

Well, Im happy to say that Ive had the privilege of living in the Third World from jungle villages to an urban shantytown on the outskirts of Lima and I can testify that what many Americans perceive as a poverty misses some important human truths.

The lack of a boombox, a wristwatch, a car, a washer-drier and a big screen color TV is not the defining measure of health or happiness. In the poor communities where I have lived abroad, I have found typically found more reliance on family, friends and neighbors; stronger religious ties; more interdependence and sharing, greater patience, tolerance and generosity. People who still tend to livestock and fields know the land intimately and are close to its rhythms. This awareness of nature is critical because they depend on soil, water and seeds rather than a convenience store for survival.

There is no denying that electric power can make life more pleasant and can provide otherwise unavailable life-saving interventions (911 emergency calls, ambulances, high-tech medical treatments). But, short of addressing life-threatening dangers, how often can we say that the benefits we draw from our profligate consumption of electricity are really essential?

The use of energy-efficient labor-saving devices (electric sewing machines, simple food processors) are liberating. The acquisition of frivolous, energy-guzzling convenience gizmos (electric can-openers, garage-door openers, big-screen TVs) are less defensible.

It is worth noting that some of the healthiest and most content people on Earth do not consume vast amounts of electricity and have no need for an excess of material wealth. Among them are the Masai of the Serengeti, the Amish of Pennsylvania, the Buddhist monks of the Himalayas and the mountain-dwelling Archuacos (the Elder Brothers) of Colombia.

The arithmetic of the worlds energy equation leads to two conclusions: (1) not everyone on Earth can consume energy like Americans and (2) not even Americans can continue consuming energy like Americans.

If there were to be energy equity among countries, everyone would aspire to live not as Americans but as citizens of Belize or Fiji, two countries that the World Bank has identified as middle income countries.

Life in a Village without Electricity

Like most US environmentalists, I spent most of my life committed to the goal of bringing electricity (preferably cheap, decentralized and renewable) to every hut and home in the world.

I never had reason to question the impacts of electrification until 1996, when I spent an evening watching a slide show chronicling the proceedings at the Third EcoCity Conference an international event that had been convened earlier that year in the coastal village of Yoff, Senegal.

Yoff is a small traditional village whose sustainable economy based on fishing and farming has remained unchanged for thousands of years. In 1864, the French commander of the Isle de Goreé spoke admiringly of the villagers indomitable passion for independence. The citizens of Yoff never signed the treaty recognizing French authority in Senegal.

Richard Register, the man behind the EcoCity Conferences (the previous meetings were held in Berkeley, California and Curitiba, Brazil), recalls his time spent in Yoff.

Walking through Yoff by starlight, we explored the narrow, nighttime streets wrapped in the dry, cool breezes off the Sahara. With no smog, no glare, the desert sky was a velvet-black treasure chest of stars sparking over the soft-sand streets

.

Yoffs soft streets create an environment in which children play more freely than Ive ever seen. Youngsters congregate on the rooftops, climb high walls, jump off, chase one another, fall down. But as a guest from the US observed, You fall down, but you dont get hurt. Sure enough, there are none of the bloody knees and elbows and dewy eyes we see in the land of asphalt and concrete.

By day, the hundreds of smiling, open-faced children run up to shake visitors hands and hold on with lingering giggles. There are none of the conversations that plague adult/child meetings in the wealthy countries exchanges hinging on pretty clothes, new toys, appearances, or the presumed suspicion of strangers.

What Happens when Electricity Hits a Village?

PERU: The view from my bedroom window in a Lima shantytown shows that electricity does not, by itself, eradicate poverty. My neighbors were not given power: They had to organize and demand it. The dirt streets were cleaner than the average paved road in the US. My neighbors were poor but they had great self-respect. Credit: Gar Smith/The-Edge |

But things were beginning to change in Yoff. Electric power lines had been hung down the main roads and now even in Yoffs soft, narrow, unlit, car-less streets new sounds were starting to drown out the old.

Register recalled how the soft streets, emptied during the heat of the day but would begin to fill with the chatter and laughter of families as the men returned from their boats and fields. Neighborhood musicians would bring out their instruments and drums. Small children would join in, singing, clapping hands and batting sticks on boards or bricks.

Around one corner, Register discovered a smiling man sitting outside with a foot-pedal-powered sewing machine. If you wanted a shirt, dress or a pair of pants, he proudly explained, he would take your measurements, you could select the fabric and he would set to work. Your new piece of apparel would be ready the next day.

Sadly, Register reported, the introduction of electricity was already beginning to erode a vibrant, village culture that had existed, relatively intact, for hundreds of generations.

With the introduction of radios and tape-players, the music had begun to move indoors. Instead of being the live, communal experience that formed part of daily life in the neighborhoods for uncounted thousands of evenings, it became something that happened inside someones home. Something that drew people away from the soft, shared streets.

The cancer of commercial media was beginning to metastasize. The terminal phase, if allowed to spread, would be the same as it has been everywhere else on Earth where the commercialisms electric seed had been planted another community of gregarious, outgoing participants transformed into a collection of isolated spectators.

Already the power-pole-lined boulevards of Yoffs nearby cities had come to resemble urban streets everywhere: crowds of automobiles; the blinking lights of small businesses selling imported cigarettes, drinks and magazines; billboards promoting the consumption of foreign merchandise; and the scatter of tossed packaging and other commercial detritus littering dirty gutters and cracked concrete sidewalks.

Soon, the tentacles of electric wire would begin to snake into the ancient homes of Yoffs quiet neighborhoods bringing the hypnotic images of TV screens to the eyes of Yoffs children.

Would these children still clamber up walls in feats of daring-do and tumble safely into the sandy carpets of Yoffs eternal streets? Of course they would. But less often.

Why Some Critics View Electricity as Zombie Juice

Running an ever-expanding economic juggernaut like the Global Economy requires turning poor communities into tomorrows consumers. In order to turn traditional, self-supporting sustainable societies into an army of dependent, product-addicted consumers, it is first necessary to undermine, subvert and destroy the pre-existing culture. And that is where television plays a critical role.

Gasoline is the fuel that powers the automobile industry.

Electricity is the fuel that powers the Consumption Economy.

As media critic Jerry Mander (author of Four Arguments for the Elimination of Television) writes in his book, In the Absence of the Sacred, Television is the way human minds are made compatible with the system and identical with one another; it is the sales system, and the audiovisual training mechanism.

As Mander and others have pointed out, television is known to induce a hypnotic passive-receptive alpha-state trance in viewers. People joke about how children and adults turn into zombies while watching the boob tube but they fail to appreciate the disturbing, underlying truth that the TV set has become the most far-reaching and effective form of mass-market mind control ever invented.

From the corporate point of view, Mander adds, the effect is beneficial.

Or, as the old joke says: Thats why they call it television PROGRAMMING.

Despite its seductive impact on the central nervous system, television need not be a malevolent device. Community-owned, nonprofit and public-service broadcasting can use TV screens to promote information exchange, local culture and democratic debate.

The problem comes with privately-run, for-profit, commercial broadcasting which, all too often, gives new meaning to the words crass, pap, and lowest common denominator. Using satellite technology to beam the broadcasts of US-based Christian televangelists or re-runs of Fear Factor or The Osbornes onto TV screens in Zamboanga, Santiago (or, for that matter, Peoria), doesnt meet the definition of benign technology.

Wealth and Health Are Not Always Linked

Most children in countries that Americans would dismiss as poverty stricken are actually healthier than many kids in America. Thanks to diets of fresh, unprocessed foods and more physically active lives, children in most Asian and Latin American countries have trimmer bodies, quicker reflexes and better teeth than the majority of US kids who increasingly suffer from morbid obesity, diabetes, sugar-rotted teeth and respiratory ailments.

The Surgeon General has warned that more than 13 percent of US children are overweight and at risk of diabetes and other life-threatening diseases. Study after study has drummed home the message that the reason we have so many fat kids (and Couch Potato adults) is because of an epidemic of lassitude linked to excessive consumption of TV programming (averaging four or more hours a day), fast foods and sugar-filled soda drinks. Coincidentally, not one of these debilitating factors would exist without the consumption of super-sized portions of electric power.

The slums, favelas, kampungs, tugurios and shantytowns of the world can be crowded with unhealthy concentrations of humanity but, in their congestion and squalor, they can be matched by many urban jungles in the worlds major electrified cities. The residents of these outposts of fringe survival realize that access to electricity is not their most important need.

Poverty of Circumstance Does Not Mean Poverty of Spirit

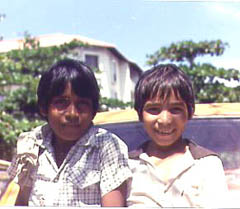

NICARAGUA: Antonio and Vladimir taught me that "roller-skate poverty" could be overcome with ingenuity and teamwork. Credit: Gar Smith / The-Edge |

On a trip to Nicaragua to report on the countrys first democratic elections in 1986, I was befriended by a couple of youngsters in the town of Granada. One day, I noticed that they only had one pair of rickety roller skates between them. When I asked how they decided whose turn it was to skate, their response surprised me.

We both do, they replied with wide smiles. They explained that if each one strapped a skate to one foot and they tied their ankles together, they could propel themselves down the street kicking with their free feet. The only other thing that was needed was the ability to hug each other tight and not double over from laughter.

This has always stuck with me as a perfect example of how friendship and close cooperation can overcome limited resources and seemingly insurmountable obstacles.

Being poor in material goods can leave one enriched in many other dimensions. The trick of modern consumption economies is that they convince people that they are being freed through the offer of limitless conveniences.

The truth is somewhat different: With the adoption of each new convenience be it a pre-cooked microwave meal or a computerized automobile that can only be serviced by a certified mechanic-cum-computer-wonk , people become increasingly less self-sufficient. The effect is that the consumer becomes trapped in a downward spiral of increasing powerlessness and dependency.

If material comfort were the only goal of human striving, why do so many materially blessed urbanites feel the need to flee the city to camp in the wilderness or hike in the Sierras? (For sobering proof of just how deeply ingrained the link of electricity and life has become, just ask someone why they choose to spend a week in the wilds. More often than not they will unthinkingly reply: I just needed to recharge my batteries.)

Our modern perspective places a great onus on living sustainable, land-rooted, community-centered lives. But if the world economy were to collapse tomorrow and all the gas pumps, ATMs and powerlines failed, who would be more adept at long-term survival the Harvard-educated businessman or the average San Bushman in the deserts of South Africa?

For more information contact:

Contact the websites and resources listed in the above article.