'Nonviolent Peace Armies' Deployed in Iraq and Sri Lanka

By Gar Smith / Common Ground Magazine

June 27, 2004

|

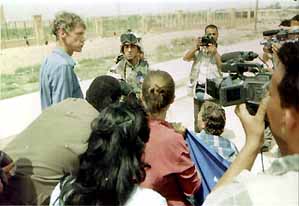

| Emergency Peace Team volunteer Peter Lumsdaine attempts to meet with US troops in Iraq. |

In the night sky above Fallujah, the drone of a 77-ton AC-130H Specter gunship nearly drowns out the wail of minaret loudspeakers raising the cry, "Allah Akabar, God is Great." It is clear to those on the ground that the US Occupation is no longer a battle for "hearts and minds" -- it has become a bloody struggle for turf.

Appalled by the civilian deaths, Peter Lumsdaine, a San Francisco peace organizer, sent out a call for volunteers willing to "nonviolently challenge the US military offensive in the holy cities of Karbala and Najaf." Two weeks later, Lumsdaine's five-member Iraq Emergency Peace Team was making its way through Naraf's rubble-strewn streets and preparing to place their bodies between the city's mosques and the Pentagon's tanks.

In addition to Lumsdaine and his wife Meg (an ordained Lutheran pastor), the Peace Team consisted of Mario Galvans, a Bay Area highschool teacher, Brian Buckley from the Catholic Worker community in Virginia and New Yorker Trish Schuh, co-founder of the Military Families Support Network.

During a visit to the mosque of rebel cleric Muqtada al-Sadr, al-Sadr's people offered to provide the peacekeepers with armed bodyguards. "They seemed to be surprised that we declined," one peacekeeper reported in an email to friends in San Francisco.

"We have heard many stories of callous brutality, ignorance or indifference to local customs and disproportionate use of force," Mario Galvans reports. Galvans cites a recent case where troops opened fire on a taxi that attempted to pass a US convoy. "Soldiers ordered them to stop but, for whatever reason -- panic, fear, not understanding the commands -- they didn't. The soldiers opened fire, killing one passenger and wounding the other."

The Peace Team's escapades may be dismissed as fool-hardy or embraced as heroic but Lumsdaine's risk-taking is not unprecedented. Recent years have seen a dazzling proliferation of citizen "peace soldiers" who have flocked to global troublespots in hopes of preventing -- or, at least, minimizing -- the carnage.

Granted, the likelihood of a small number of courageous and determined individuals derailing a billion-dollar military juggernaut is slim, but a growing number of theoreticians are raising an intriguing question: "What might happen if the world had a standing nonviolent army of thousands?

[For background on the strategies behind civilian peacekeeping, see "The Roots of Nonviolence" in Flotsam & Jetsam.]

|

The Nonviolent Peaceforce team in Sri Lanka. (Back row, from left: Midori Oshima, Charles Otieno, Karen Ayasse, Linda Sartor, Soraia Makhamra, Susan May Granada. Seated, from left: Frank Mackay Anim-Appiah, Sreeram Sundar Chaulia, Thomas Brinson, Angela Pinchero, Rita Webb.

|

Mel Duncan's Road to Peacemaking

As the father of eight adopted children, Mel Duncan clearly has a stake in the future. This veteran community organizer from St. Paul, Minnesota doesn't come across as a firebrand. Instead, the cherubic, puckish Duncan is blessed with a jokester's genial mien and the easy smile of a born salesman.

"Meister Eckhart is one of my role models," Duncan grins. Eckhart was "pro-peace, pro-woman, pro-peasant," but more importantly, "Eckhart realized that the peasant class represented a powerful historic force that could not be denied."

On February 15, 2003, Duncan saw "15 million self-organized citizens marching for peace from Auckland to Oakland." The message was clear. "We can do this. The ingredients abound. There are peace movement vets around the world -- in Kenya and the Philippines. If you look around the world, you'll discover that most 'peace warriors' are women."

Duncan first had his vision of a global peaceforce during a stay at the Buddhist monastery where Thich Nhat Hanh teaches. It was one of Duncan's Sufi teachers who gave him his nonviolent marching orders: "Your job is to enlighten the heart of the enemy."

For 30 years, Duncan admits, "us-versus-them was my operating assumption. My approach wasn't fundamentally different from George W. Bush," Duncan chuckles. "I just chose better enemies."

Drawn to the study of Buddhism, Duncan slowly came to understand that head-to-head battles were not as effective as heart-to-heart encounters. He recalls how one day, while walking with one of his spiritual mentors, he informed her rather immodestly: "I'm making good progress on resolving my duality." His companion looked at him with an amused smile and replied: "So you still believe it exists?"

"Western debaters try to dominate their opponents," Duncan now realizes, whereas "Eastern debaters try to illuminate their opponents. We can no longer chose sides. We have to come from a position of common unity."

In 1999, Duncan attended the Hague Peace Conference in hopes of promoting his vision. But before Duncan could commandeer a microphone, a stranger stepped up to the podium to propose the creation of "nonviolent peace force."

Duncan was astonished. The speaker was San Francisco's David Hartsough. Duncan raced to his side, introduced himself, and forged a life-altering friendship.

Hartsough's Journey: From Gandhi to Kosovo

David Hartsough's Quaker parents set him on his spiritual path when they introduced him to the writings of Mahatma Gandhi at an early age. Now a veteran of the Civil Rights and anti-war movements the tall, quiet and still-boyish Hartsough is fully aware of the risks of nonviolent witness.

When Hartsough was in his 20s, he participated in a sit-in to desegregate a southern restaurant. When an enraged racist threatened to kill him with a switchblade, Hartsough told the man: "Do what you think is right and I'll try to love you no matter what." The man's knife and jaw both dropped and he walked away dumbfounded.

A decade later, Hartsough was with Vietnam veteran and anti-war activist Brian S. Willson when a Bay Area peace protest at went horribly wrong. Willson was sitting cross-legged on the tracks just outside the Navy weapons station at Port Chicago, hoping to block a train carrying explosives to El Salvador. Unbeknownst to the protestors, the military had ordered the train operator not to stop. The locomotive barreled over Willson, severing both his legs.

Willson went on to become an iconic figure of the anti-war movement and Hartsough went on to found the San Francisco's Peaceworkers organization, which has sent nonviolent intervenors to Chiapas, Mexico and Kosovo, Yugoslavia.

During the NATO bombing campaign, Hartsough and five other Peaceworkers were thrown into a Serbian jail for several days, causing an international incident. Hartsough emerged from that Serbian cell determined to build a global peace army.

How It Would It Work

The NPF is convinced that "third-party nonviolent intervention is humanity's greatest chance to mobilize civil society against the war system and finally to bring it to an end."

"There are other, older groups that have put nonviolent activists into troubled areas," Duncan concedes. "There's Witness for Peace and Voices in the Wilderness. But the Nonviolent Peaceforce is unique in that its members are paid a salary -- $800 a month for duty in Sri Lanka."

The Nonviolent Peaceforce (NPF) would consist of 2,000 paid professionals, 4,000 reservists and 5,000 volunteers -- all backed by an administrative organization and a research and training staff. Professional peace soldiers enlist for a two-year tour of duty. "We hope to have 50 NPF members on the ground by the end of 2004," Duncan states. "Beyond that, we would like to have 2,000 unarmed civilian NPF members by the year 2010."

Within three years of its founding, the NPF had won the support of the Dalhi Lama and seven Nobel Peace Laureates. The NPF now has home offices in St. Paul and San Francisco and, as Duncan proudly notes, "ninety-two groups on every continent but Antarctica."

Hartsough estimates that it will take $1.6 million a year to finance the NPF. This seems like a lot until Hartsough points out that this is less money than the Pentagon will spend in the next two minutes. "With one-tenth of 1 percent of the US military budget," Hartsough argues, "we could have a full-scale nonviolent peaceforce able to intervene in conflict areas in many parts of the world." And, he adds, it would be able to respond more quickly than UN peacekeeping forces.

The Mission to Sri Lanka

In December 2002, NPF reps from more than 40 peace and nonviolence organizations convened near New Delhi and selected Sri Lanka as the site for the NPF's first pilot project. Sri Lanka's People's Action for Free and Fair Elections extended the invitation. (The NPF, unlike the US Marines, only goes to countries where it has been invited.)

During its 20 years of civil war, Duncan claims, "Sri Lanka has seen more suicide bombers than Israel and Palestine." The country is beset by landmines, child soldiers, and abductions but a cease-fire -- the fourth in 20 years -- seemed to offer a window of opportunity.

Duncan is realistic about the ultimate impact of NPF troops: "People have to make their own peace," he admits. "Outsiders can, at best, provide support and protection."

Fourteen people from 11 countries formed the first team. Members ranged young adults to a Vietnam veteran. The NPF dispatch two teams to Jaffna in the north (with members from Kenya and Philippines), a team to Martara in the south (Ghana, Japan and US) and a team to Muthur and Trincomalee in the east (Brazil, Palestine, Germany, US).

In Sri Lanka, conflicts rage not only along religious lines (Christians versus Muslims) but also along linguistic lines, with Tamils and Singalese speakers frequently identified as enemies solely because of the language they speak. Consequently, Peaceforce members had to learn both basic Tamil and Singalese in a grueling four-week crash course.

Linda Sartor: A Peacekeeper in Valachchennai

Following the September 11 attacks, Linda Sartor, a former middle-school teacher from Sonoma County, found herself "tormented" by Washington's violent bombardment of Afghanistan. Suddenly marching no longer seemed sufficient. "I was ready to demonstrate with my body that my life is no more precious than the lives of the people in countries terrorized by the US." Sartor went to Palestine with the International Solidarity Movement and later flew to Iraq to witness with other international before the start of the US invasion.

Last November, Sartor enlisted in the NPF and soon found herself in Sri Lanka navigating streets clogged with "pedestrians, bicycles, cows, goats, dogs, cats, buses, vans, trucks, three-wheelers, ox-drawn carts and very few cars." Sartor's team was stationed in the village of Valachchennai, where Muslims and Tamils ran separate civic offices, schools, buses and some neighbors remain so distrustful that they haven't spoken for a generation.

The roads in the Batticaloa district were lined with the humps of crushed houses and tangled lanes of barbed wire. The NPF set up its office on a street "lined with Moslem shops on one side and Tamil shops on the other" in hopes that "the presence of three foreigners there could make a difference in the fears and tensions."

Adding to the tensions, Sri Lankan President Chandrika Kumaratunga had just suspended parliament. Violence flared soon enough as a partisan march ended with political candidate burned in effigy near the NPF office. This was followed by two attempted assassinations and the slaying of the local Tamil National Alliance candidate who was murdered in his home after completing his morning prayers.

Shops were closed, one Tamil-owned store was set afire and looters prowled the streets, NPF staffers rushed to visit people who needed protection and reached out to local contacts to arrange a "public vigil in support of nonviolence."

On April 9, a bloody confrontation erupted between political factions facing off on either side of the Verugal River on the border between the Battacaloa and Trincomallee Districts. The local NPF team found itself "dealing with the civilian catastrophe that resulted." As the only group of internationals in the area, NPF labored throughout the day, working with clergy, government officials and the army to ensure shelter, food and water for civilian refugees, some of whom had walked 20 kilometers to reach safety.

The approach of the March elections provided NPF with another test -- several weeks of pre-election monitoring and repeated visits with police and military officials as well as the Muslim residents of several Internally Displaced Persons camps.

On election day, NPF teams rose before dawn to visit more than 30 polling stations during the eight-hour voting period. NPF workers labored into the night, accompanying ballot boxes to counting stations and monitoring the counting of ballots. The outcome was reported in an official dispatch dated April 12, 2004: "Despite the gloomiest of forecasts, the election was the most violence-free that Sri Lank had had for some time."

Meanwhile, in Najaf, the war clouds continued to gather as the restive US military waited to unleash its awesome firepower in another wave of "defensive strikes." And, in the crosshairs of this potential killing ground, Peter Lumsdaine and his Emergency Peace Team were standing firm.

"We understand the dangers of our journey, but we are determined to try and contribute in our own small way to peace and justice for the people of Najaf," the Peace Team's collective statement reads. "Only when peacemakers are willing to shoulder some of the same risks that soldiers take in war, can we begin to move away from the cycle of violence that grips human society at the dawn of the 21st century."

While George W. Bush contends that there is no alternative to a future of endless war, the NPF "is quietly attempting to institutionalize a proven alternative." If it succeeds, "the world will have two kinds of standing armies to choose from."

A shorter version of this article first appeared in the June 2004 issue of Common Ground magazine. [www.commongroundmag.com]

Peaceforce Resources

Nonviolent Peaceforce, 801 Front Avenue, St. Paul, MN 55103, (651) 487-0800. www.nonviolentpeaceforce.org

Peaceworkers, 721 Shrader St., San Francisco, CA 94117, (415) 721-0302.

Witness for Peace www.witnessforpeace.org

Peace Brigades International www.nonviolentpeaceforce.org

Christian Peace Team www.cpt.org

Voices in the Wilderness www.vitw.org

International Solidarity Movement www.palsolidarity.org

For more information contact: