Pumping Irony: How Political Campaigns Sell the Sizzle, Not the Mistakes

By John Stauber and Sheldon Ramptom

October 4, 2004

|

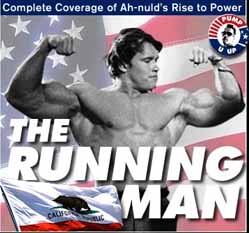

| Lights, Camera, Auction! Arnold Schwarzenegger's multi-million-dollar gubernatorial campaign was a classic example of modern political media manipulation. |

For Jay Leno, it was a big night. Movie muscleman Arnold Schwarzenegger, was coming on The Tonight Show to announce whether he would run in California's recall election against Governor Gray Davis.

Bounding onstage, Schwarzenegger began with a warm-up joke, then he got serious. "The politicians are fiddling, fumbling and failing," Schwarzenegger said. "The man that is failing the people more than anyone is Gray Davis... and this is why I am going to run for governor." The announcement prompted cheers from Leno's studio audience and Schwarzenegger rewarded them with some of his famous movie lines. "Say hasta la vista to Gray Davis," he said, promising to "pump up Sacramento."

Schwarzenegger's Tonight Show remarks were carefully crafted by Republican pollster Frank Luntz. In a memo, Luntz outlined 17 ways to "kill Davis softly." While it was important to "trash the governor," he advised, "issues are less important than attributes and character traits."

Campaign consultants advise that the best way to go negative is to find a lighthearted way to do it. As Democratic campaign operative Deno Seder explains, humor "induces the flow of endorphins and other brain hormones, creating a sense of wellbeing or euphoria.... Leaving them laughing creates a feeling of goodwill toward the sponsor, while actually accentuating the sting of the attack on the opponent."

Republicans have shown a mastery of the rules of postmodern politics, in which style is as important as substance and issues are less important than personality. Republican candidates understand these unwritten rules because their campaign consultants, some of whom actually started in the entertainment industry, played a big part in inventing them.

Schwarzenegger's liberal views on abortion and gay rights were accepted by party activists as pragmatic necessities, given California's cultural environment. As strategist Matt Cunningham explained, "When a man is lost in the desert and dying of thirst, he's not going to insist on Perrier."

The Running Man

Newspapers and serious television news shows were, for the most part, ignored by the Schwarzenegger camp, which waited until 30 days into his campaign before agreeing to his first interview with California newspapers. Instead, carefully crafted messages were relayed to the public via Access Hollywood, The Oprah Winfrey Show, The Howard Stern Show and Larry King Live. According to Sean Walsh, the campaign's co-director of communications, "We ran away from the established media. We went to the real mass media.... It gave us five, seven, eight minutes of unfiltered opportunities to get out our message every day."

The day after his election, the governor-elect returned to The Tonight Show. During his unbilled (but clearly preplanned appearance), Leno's band played "Happy Days Are Here Again."

"What Leno's presence did is give legitimacy to the notion that it wasn't a partisan event, it wasn't a political event, it was somehow an American cultural event," says Marty Kaplan, associate dean of the University of Southern California's Annenberg School for Communication. "It was like welcoming home an astronaut from a safe voyage. In so doing, it played into a campaign strategy that this was a campaign for all, beyond politics. Which is not true; he's a Republican candidate.... It gives the impression of taking it out of the political realm into an extraterrestrial domain where politics don't matter, where we're all friends. It puts people who value dispute and debate [into the position] where we're all seen as earthly and petty, as if we should get with the program."

Dancing Elephants: Political Life after Sit-coms

Conservatives decry the "liberal bias" of the mass media. It is true that people from these industries give about two-thirds of their campaign contributions to Democrats, and one-third to Republicans -- while leading corporate sectors such as oil, livestock, trucking, chemicals, tobacco, railroads and the automobile and restaurant industries, give more than 70 percent of their contributions to Republicans.

While there is no shortage of liberal performers in Hollywood, Democratic-leaning actors have rarely sought political office. The only examples are Sheila Kuhn, a California state senator who had been a child actor on The Many Loves of Dobie Gillis (from which she was fired when CBS discovered that she was a lesbian) and Ben Jones, who played Cooter on the Dukes of Hazzard before serving two terms as a Democratic US congressman from Georgia.

By contrast, acting has been a stepping-stone to political careers for many Republicans, including: George Murphy (US senator from California); Ronald Reagan (California governor and two-term president); Clint Eastwood (mayor of Carmel, California); Fred Grandy (Gopher on TV's The Love Boat and Iowa congressman); Sonny Bono (mayor of Palm Springs and US Congressman); Fred Thompson (the US Senator from Tennessee who appeared in The Hunt for Red October, In the Line of Fire and as a district attorney on NBC's Law and Order).

California: Birthplace of the Political Campaign

The first modern political-campaign firm, Campaigns Inc., was established in California in the 1930s by the husband-and-wife team of Clem Whitaker and Leone Baxter.

Whitaker and Baxter drew on the culture of nearby Hollywood as they developed techniques for "selling" candidates through the mass media. Incumbent California governor Frank Merriam hired Whitaker and Baxter to defeat a 1934 election challenge by muckraking journalist and social reformer Upton Sinclair. Whitaker and Baxter developed a smear campaign to defeat Sinclair, arranging to have false stories printed in newspapers about Sinclair seducing young girls.

To combat Sinclair's Depression-era populism, they worked with Hollywood studios (which controlled movie theaters throughout the state) to place phony newsreels in cinemas featuring fictional "Sinclair supporters" in rags advocating a Soviet-style takeover.

After their victory, Whitaker and Baxter explained the cynical philosophy behind their success: "The average American doesn't want to be educated, he doesn't want to improve his mind, he doesn't even want to work consciously at being a good citizen. But every American likes to be entertained. He likes the movies, he likes mysteries; he likes fireworks and parades. So, if you can't put on a fight, put on a show."

Whitaker and Baxter transformed elections from "a hit or miss business" into "a mature, well-managed business founded on sound public relations principles, and using every technique of modern advertising."

The Rise of Richard Nixon

Whitaker and Baxter were succeeded by another Californian, Murray Chotiner, who took Richard Nixon under his wing in 1945 and groomed him in the techniques of political campaigning.

"It was Nixon's television performance in his Checkers speech that saved his place as Dwight Eisenhower's running mate in 1952," notes historian David Greenberg, the author of Nixon's Shadow: The History of an Image. "In a historic piece of image-craft, Nixon talked earnestly about his onerous childhood and his struggles upon returning from the Navy -- and adorned his speech with folksy touches about his wife's cloth coat and his daughters' cocker spaniel.

Following his 1960s election defeat against John F. Kennedy, Nixon hired professional image-manipulators including New York public relations executive William Safire, advertising executives H.R. Haldeman and Harry Treleaven; and television producer Roger Ailes (currently the head of Fox News).

The problem for the Nixon campaign, Ailes said, was that Nixon was "a funny-looking guy. He looks like somebody put him in a closet overnight and he jumps out in the morning with his suit all bunched up and starts running around saying, 'I want to be President.'"

To change this image, the campaign produced a series of television shows in which Nixon fielded questions from panels of citizens. Although the shows were broadcast live, both the audiences and the panel were prescreened by the campaign -- just enough blacks, for example, but not too many -- and since the audience was all Republican, applause was guaranteed.

During a discussion with Harry Treleaven about whether to allow reporters to watch the tapings, Ailes insisted that it was "our television show and the press has no business on the set. And goddammit, Harry, the problem is that this is an electronic election. The first there's ever been. TV has the power now....You let [reporters] in there with the regular audience and they see [the show's warm-up man] out there telling the audience to applaud and to mob Nixon at the end, and that's all they'd write about it."

In 1968, Nixon's success in reinventing himself as the "New Nixon" helped him win the White House.

Ronald Reagan: From Re-runs to Willie Horton

In 1980, Ronald Reagan became the first actor ever to become president.

Reagan also relied on Ailes, who served as a consultant to his 1984 re-election campaign. Ailes oversaw production of the legendary "Morning in America" ads featuring swelling violin music and emotional, issue-free imagery of weddings, flag-raising, home-buying and peaceful, scenic vistas.

In 1988, Ailes worked with Lee Atwater to mastermind George H.W. Bush's come-from-behind victory over Michael Dukakis. The most egregious ads featured a threatening photograph of William Horton, a black inmate who had escaped from a prison-furlough program and raped a woman, to suggest that Dukakis was soft on crime. A second ad depicted a "revolving door" through which a line of white men entered prison, while blacks and Hispanics exited.

"That phrase 'revolving-door prison policy' implies, of course, that Massachusetts criminals could, thanks to Governor Dukakis, slip out of jail as easily as commuters streaming from a subway station," observes Mark Crispin Miller. "But the image makes an even more inflammatory statement.... The 'revolving door' effects an eerie racial metamorphosis, implying that the Dukakis prison system was not only porous, but a satanic source of negritude -- a dark 'liberal' mill that took white men and made them colored."

True Lies: Leslie Stahl Learns a Harsh Lesson

Because television is expensive to produce and broadcast, the technology lends itself to control by the people who can afford to pay for the considerable costs of production. It is also a highly emotional medium. Unlike print, which requires that the audience make a conscious effort, television is often absorbed unconsciously, as pure images and background in our information environment.

Reporter Leslie Stahl tells a story in her memoir, Reporting Live, of an experience she had in 1984 when she broadcast a piece for the CBS Evening News about the gap between rhetoric and reality under the Reagan administration. She showed staged photo opportunities in which Reagan picnicked with ordinary folks or surrounded himself with black children, farmers and happy flag-waving supporters. These images, she pointed out, often conflicted with Reagan's actual policies.

"Look at the handicapped Olympics, or the opening ceremony of an old-age home," Stahl reported, "No hint that he tried to cut the budgets for the disabled or for federally subsidized housing for the elderly."

Stahl's piece was so hard-hitting that she "worried that my sources at the White House would be angry enough to freeze me out." Much to her shock, however, she received a phone call immediately after the broadcast from White House aide Richard Darman who had just watched the piece with Treasury Secretary Jim Baker, White House press secretary Mike Deaver and Baker's assistant, Margaret Tutwiler. Rather than complaining, they were calling to thank her. "Way to go, kiddo," Darman said. "What a great story! We loved it."

"Excuse me?" Stahl replied, thinking he must be joking.

"No, no, we really loved it," Darman insisted. "Five minutes of free media. We owe you big time."

"Why are you so happy?" Stahl said. "Didn't you hear what I said?"

"Nobody heard what you said," Darman replied. "You guys in Televisionland haven't figured it out, have you? When the pictures are powerful and emotional, they override if not completely drown out the sound. Lesley, I mean it, nobody heard you."

Stahl was so taken aback that she played a videotape of her segment before a live audience of a hundred people and asked them what they had just seen. Sure enough, Darman was right. "Most of the audience thought it was either an ad for the Reagan campaign or a very positive news story," Stahl recalled. "Unlike reading or listening to the radio, with the television, we 'learn' with two of our senses together, and apparently the eye is dominant. When we watch television, we get an emotional reaction. The information doesn't always go directly to the thinking part of our brains but to the gut. It's all about impressions, and the White House understood that."

The George W. Bush administration also understands this lesson. At the Republican National Convention that nominated Bush in 2000, only 4 percent of the actual delegates were black (compared to 20 percent at the Democratic Convention) but the talent onstage looked quite different: Colin Powell, comedian Chris Black, the Temptations, a gospel choir, rhythm and blues and salsa singers, and Representative J.C. Watts (the only black Republican in Congress).

"It's all visuals," Karl Rove told campaign finance chief Don Evans. "You campaign as if America was watching TV with the sound turned down."

Excerpted from Banana Republicans: How the Right Wing Is Turning America into a One-Party State. Reprinted with permission of the authors. © Center for Media & Democracy, 520 University Ave., Suite 227, Madison, WI 53703; phone (608) 2609713. www.prwatch.org

For more information contact: