Taking the Toxic Tour: Part 1

By Gar Smith / The-Edge

January 28, 2005

|

| Denny Larson with a team of young activists in Richmond, armed with an air-sampling bucket and on the prowl for polluters. |

"Contra Costa is a potential Bhopal," Denny Larson grimaces as his red Subaru roars north on Hwy 580. "We are now entering Richmond and we may not return alive." His tone is melodramatic, but he's not entirely joking.

Between 1989 and 1997, 55 major industrial accidents rocked the county -- one every two months. For years, residents have complained bitterly -- and hoarsely -- about the seemingly endless outbursts of flares, flames, eruptions and blasts that sting their eyes and shower their rooftops with chemical dust.

Taking a trip with Larson (the force behind the famed refinery-busting Bucket Brigades) is like accepting Morpheus' challenge to Swallow the Red Pill. With Larson at the wheel of a car full of wide-eyed non-Richmond Neophytes, The Matrix of innocent-looking buildings lining the 580 corridor quickly dissolves to reveal the disturbing reality hidden behind the familiar mirage.

"This freeway was used to remove low-income residents and to form a barricade to allow high-profile residential development along the Bayfront," Larson/Morpheus reveals.

Unlike the Matrix's Morpheus, Larson is no scowling, bullet-headed, muscle-mass dressed in black. He is large, easy-going and genial. His ready smile is framed between a goatee and a tan, green-billed baseball cap. Today he sports a green-and-gray Springbok Rugby Jacket -- a momento from a recent Bucket Brigade foray to South Africa.

"You'll notice there are no big smokestacks chugging out pollution," Larson observes, "Some companies have gotten very clever." With a nod, Larson indicates one faceless structure on the left that sported a pleasant-looking greenhouse. "That's Zeneca," he reveals. "They manufacture pesticides that are known to cause cancer. And they also make cancer treatment drugs -- so it's a full-service cancer-cluster."

California is right behind Texas as the state with the greatest concentration of refineries -- five major refineries in the Bay Area alone. Since 80 percent of all oil US refineries operate in violation the Clean Air Act, that means that more than 67 million residents in 36 states are routinely exposed to the effluvia of refineries. Most of these victimized citizens tend to inhabit low-income, minority communities.

There are currently around 400 pollution sites in Richmond and "it goes up all the time," Larson informs. Particulate air pollution is the biggest single cause of death after cigarette smoking. Twenty-five percent of American adults are now afflicted with asthma; childhood asthma tripled between 2000 and 2003.

With 47,000 employees in more than 180 countries, ChevronTexaco is the world's fifth largest integrated energy company. Its annual sales and operating revenues top $120 billion. The company's website prominently displays its corporate credo. "The Chevron Way" states, in part: "Our goal is to be recognized and admired everywhere for having a record of environmental excellence."

In 1999, following a series of devastating chemical spills, a Chevron spokesperson told the press: "We would never do anything to intentionally create an unsafe situation" and, furthermore, "there hasn't been anything identified as far as there being any significant risk posed by this refinery."

Numerous health studies disagree. One 1985 federal health research institute study cited "a strong positive association between the degree of residential exposure and death rates from cardiovascular disease and cancer," particularly in Richmond and Rodeo.

"Most refinery toxic air pollution is from product leaks in equipment not smokestacks." Larson complains that the companies would rather spend millions churning out press releases than buying better valves and turning off gas releases.

Sure, there are inspections, Larson concedes, but the debate is always, "How clean is clean?" In areas like Richmond, with low-lying groundwater, spilled toxics can migrate quite easily. Testing is usually "insufficient by a wide margin" and seems designed to reach the solution "that's already politically decided."

|

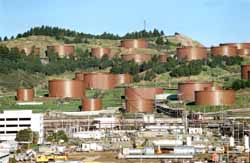

| Chevron's Richmond Refinery painted its silvery tanks brown so they wouldn¹t be such an eyesore. As a result, the tanks grew hotter and released more fumes, which created even more sore eyes. |

The Power of an Empty Bucket

In the David-and-Goliath battle between Big Industry and the Little Guy, who could have guessed that David's slingshot would someday be replaced by grandmothers armed with plastic buckets.

The Bucket Brigades began in 1995 after attorney Ed Masry and Erin Brockovich were sickened by fumes from a Unocal refinery near the homes of some clients in Rodeo. When federal officials insisted their air-samples showed no problem, an angry Masry hired an engineer to build a cheap air-testing device that any ordinary citizen could use.

Larson helped Masry put those first buckets into the hands of Contra Costa residents and, in 1996, he convinced the EPA to fund the first Bucket Brigade with a $260,000 grant. On March 25, 1999, the buckets were put to good use sampling a sky blackened by a blaze at Chevron's hydrocracker unit and they've been bagging evidence ever since.

"Air monitoring is not easy," Larson admits. "At first, it was thought that community members couldn't do it." Industry tried to dismiss the brigades as alarmist and unreliable and demanded official tests to discredit the bucketeers. Instead, the tests wound up confirming the citizen's sampling results.

Larson proceeded to introduce the buckets to refinery communities in Ohio, Pennsylvania, Texas and Louisiana. There are now 24 bucket brigades across the US. Larson tends to work with each new group for the first three years "to get them going" then he happily steps back and lets the local groups take over the monitoring chores. "For me," Larsen says, "success is seeing others quoted more in the news stories than me. When the little guys from the poor towns make the front page, that's success for me."

Into the Heart of Richmond

"North Richmond is on the frontline of chemical assaults," Larson barks, steering off 580's concrete swath and decelerating down the Garrard turnoff. After 18 years of local activism, Larson knows Richmond's history intimately. He started work in 1984 canvassing Contra Costa's "cancer belt" door-to-door with Citizens for a Better Environment (CBE).

In 2001, he hatched the Refinery Reform Campaign (a project of the Global Community Monitor/Tides Center) to lead a national campaign to clean up America's oil refineries and reduce US dependence on fossil fuels. Since starting the Global Community Monitor, Larson has become a regular Johnny Bucketseed, crossing the globe to introduce air-sampling buckets around the world.

Larson snaps open a map dotted with black skulls. "Every site represents a toxic waste, air pollution site, or chemical spill," he explains. "There are probably ten or 50 more that could be visited." A full Toxic Tour can take seven hours. Our quick-course will take four.

Downwind from Chevron's refinery, we move through downtown Richmond's blocks of empty buildings. What once was a jewelery store is now a church. We pass a burned out car and come upon a police bust. This is the Bay Area's "most depressed, lowest income, highest unemployment community." African-Americans have dominated the population since the war-industry boom of the 1940s but today, Asians and Latinos have become a sizable block of Richmond's ethnic mosaic.

"I do these tours about once a month," Larson explains, "and every time, I find something new. On the last tour, there was a 'For Sale' sign up at Drew Scrap Metal, a Superfund site. I contacted Henry Clark at West Country Toxics Coalition (WCTC). Henry raised some questions and the sign disappeared. I suspect the site could have been sold and developed without the state ever knowing about it."

Sure enough, when Larson pulls up at Drew Scrap Metals site at 7th & Castro, there's a surprise: The 'For Sale' sign is back up. Approaching the fenced-off lot, Larson explains how the previous owners used to dump scrap metal, chemicals and batteries directly on ground. Lead, cadmium and other heavy metals seeped into soil and the African-American families who lived next door all slowly died of cancer.

After the neighbors began complaining -- and dying -- the county tested the vegetables in a nearby family garden and found dangerous concentrations of lead, cadmium and other heavy metals. After the lot was declared a Superfund site, the poisoned soil was covered with "clean dirt" and capped with asphalt. Unfortunately, a stream runs alongside the property, so the capped chemicals simply drained into the creek.

"Whether that's a clean-up or a cover-up is debatable," Larson snorts. "This was the first site in California where they tried [cover-and-cap] and got away with it." Cover-and-cap soon became a model for other states. Today, the warning signs on the chain link fence surrounding this Superfund site are weathered and unreadable. If this site is ever sold, Larson suggests, the owner should be required to repay the state for the clean-up.

At Second and Nevin, a small boy stands on the stoop of a house with a broken window, staring impassively as Larson parks. The Electro-Formatting building sits directly across the street from a row of homes. Here, on August 22, 1992, a tank ruptured and released a cloud of nitric acid that blanketed 20 neighborhood blocks and sent more than 100 people to the hospital. Larson indicates the Prop 65 signs on the building, warning of the presence of toxic compounds. "You notice the signs dont have an 800 number," he adds.

The next stop is General Chemical where, on July 26, 1993, a preventable industrial accident caused "our closest Bhopal." Ten steps from where Larson has parked, workers behind a metal gate are unloading a chemical tank car. Back in 1993, workers were having trouble unloading a car filled with oleum. They were told to heat the thick material to 120F to get it to flow.

Unfortunately, Larson relates, they had to use a gauge that only went to 50F and "it went around six times while the workers weren't looking." The resulting explosion emitted a choking cloud that spread more than 17 miles and sent 25,000 residents to local hospitals.

ChevronTexaco's Output

ChevronTexaco processes more than 300,000 barrels of oil a day on its sprawling 2,900-acre petroleum ranch. In an average year, the refinery pours a million pounds of toxics into the air and 500,000 pounds into the bay, making it one of the state's Top Five chemical polluters.

Between 1991 and 1999, the refinery racked up ten serious chemical releases. On March 25, 1999, an explosion sent 18,000 pounds of corrosive airborne sulfur dioxide over the Triangle Court neighborhood. The smoke killed trees, burned the fur off squirrels, and sent hundreds of blinded, vomiting residents to hospitals.

For years, Chevron dumped benzene, toluene, xylenes, chromium, lead, vanadium, nickel and volatile hydrocarbons onto five "landfarms" installed a mile upwind from homes, an elementary school and a playground. Of the 22 public housing projects in Contra Costa's "Gasoline Alley," six (mostly Black and Latino) are at high risk from exposure to chemical pollutants. The minority communities of Triangle Court and Las Deltas sit directly downwind from the refinery. Curiously, none of the predominantly white housing projects are located within a mile of a chemical site.

"It's no accident that dangerous fires, explosions and toxic spills continue to increase when refineries are calling the shots and monitoring themselves," Larson charges. A "tax-on-toxics" would help but, since ChevronTexaco and its industrial ilk comprise the city's major employers, Larson fumes, the city won't even approve liability insurance," even though "a gazillion toxic industries are driving a death wagon right through these neighborhoods every day." You need a license to drive a car, Larsen reasons, so "not to demand insurance for chemical plants defies logic." Chevron contends that taxing industry will drive away jobs and business. Larsen's response: "The last time I looked, state auto insurance doesnt seem to keep people from driving their cars."

"The 32 local neighborhood councils are a real cool part of Richmond," Larson smiles. "And there are more churches than any other kind of establishment -- a church on every corner, sometimes two. That's a very positive thing in the community. But the power of Chevron is so great..." At one point, Chevron even argued that it should be exempt from monitoring because its emissions were "trade secrets."

Politically, North Richmond remains a "jurisdictional nightmare... a community divided, literally, in half. The people have no redress with the local mayor or city council. Instead, they have to travel all the way to Martinez to the Board of Supervisors where they are just one of 75 or100 other unincorporated areas all pleading for help."

Continued: Please go to Taking the Toxic Tour, Part 2: "The View from Richmond Parkway."

A shorter version of this article is featured in the February issue of Common Ground magazine (www.commongroundmag.com).

For more information contact: