The Tsunami and the Brandt Report: Part 1

Mohammed Mesbahi and Dr Angela Paine

Share the World's Resources

April 3, 2005

|

| Tsunami victims. North of Sci Lanka, Mullaitivu District. Credit: J. Van Heerden International Committee of the Red Cross |

The response of the world public to the tsunami disaster on the December 28, 2004 continues to be) one of heartfelt empathy and an instinctive desire to help fellow human beings in trouble. Never before have so many people, from so many countries given so much to the victims of a disaster. World governments have been shamed into promising far greater sums of aid than they originally wanted to offer by the sheer magnitude of the public's generosity.

The US initially pledged $15 million but, in the end, promised $350 million while the British government felt obliged to raise their pledge to $96 million -- still a tiny fraction of the money these governments have so far spent on the war in Iraq ($148 billion for the US and $11.5 billion for the UK). As British journalist George Monbiot says, the UK has spent almost twice as much on the war in Iraq as it spends annually on aid to the Third World. The US gives just over $16 billion in foreign aid: less than one-ninth of the money it has so far burnt in Iraq.

How many people realize, however, that many of the deaths caused by the Tsunami could have been prevented? The area affected has been hit by tsunamis in the past, with far fewer deaths because the coastlines of Southeast Asia were protected by a natural defense system, composed of coral reefs and mangrove forests. Many of the previous tsunamis were tamed by the coral reefs before hitting the coast, where they were absorbed by a dense layer of red mangrove trees. These flexible trees, with long branches growing right down into the sand below the surface of the sea, absorb the shock of tsunamis. Behind the red mangrove trees, there is a second layer of black mangrove trees, which are taller and slow down the waves.

Thousands of miles of coastline in Southeast Asia were densely covered in mangrove forests, protecting the coastline from erosion, absorbing carbon dioxide and providing a breeding ground for crustaceans and fish, on which the local population depended for their livelihood. This was a fragile environment, which ecologists have long recommended should enjoy special protection. In India a Coastal Regulation Zone (CRZ) was created to protect a 500-meter buffer-zone along the coast.

While the belt of mangrove forest still existed, the people of the area lived inland, behind it. In 1960, a tsunami hit the coast of Bangladesh in an area where the mangroves were intact. No-one died. These mangroves were subsequently cut down by the shrimp (prawn) farming industry. In1991, thousands were killed when a tsunami of the same magnitude hit the same region.

On December 26, 2004, Pichavaram and Muthupet, two coastal villages in South India that still have their mangrove forests, suffered fewer casualties than the surrounding mangrove-less areas of coast. Mangroves also acted as a barrier, helping people to survive on Nias Island, Indonesia, close to the epicentre of the December tsunami. Burma and the Maldives suffered less from the tsunami because the shrimp and tourism industries had not yet destroyed all their mangroves and coral reefs.

Shrimp Farms, Tourists and Dynamite

Since the 1960s, the mangrove forests of Southeast Asia have been systematically destroyed to make way for commercial shrimp (prawn) farming and a massive increase in the tourism industry. The aquaculture and tourism industries succeeded in diluting any protective regulations that were in place, until they were able to take over most of the buffer zone. Almost 70% of the region's mangrove forests have now disappeared.

Since three-quarters of Southeast Asian commercial fish species spend part of their lifecycle in the mangrove swamps, the loss of these swamps has resulted in declining fish harvests. To compound this situation, the commercial feeds, pesticides, antibiotics and non-organic fertilizers used in intensive shrimp farms have generated huge amounts of pollution, destroying the remaining fish and harming the coral reefs.

As the fish have declined, desperate fishermen resorted to dropping dynamite into the reefs to drive them out. Scientists working for the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) have recently compiled The World Atlas of Coral Reefs, an underwater survey. They found that one-third of the world's coral reefs are in South-east Asia and almost all are under threat. 70% of the world's coral reefs have already been destroyed. 80% of Indonesia's reefs are in danger. Dynamite fishing has contributed to the destruction of an ecosystem already under threat from sediment erosion caused by the loss of mangrove forests, shrimp-farm pollution and untreated sewage from the tourism industry.

According to Susan Stonich, a California University professor, international corporations, based in the First World but operating in the Third World, produce 99% of farmed shrimp. Almost all of it is eaten in the US, Western Europe and Japan, where consumption has increased by 300% in the last ten years. Today world shrimp production, in an industry worth $9 billion, is almost 800,000 metric tons and 72% of farmed shrimp comes from Asia.

The NGOs versus the Industry

Hundreds of nongovernmental organizations have sprung up at local, national and international levels to oppose this destructive aquaculture industry. In 1997, the Industrial Shrimp Action Network (ISA Net) was formed, a global alliance opposed to unsustainable shrimp farming. Aquaculture corporations responded by forming the Global Aquaculture Alliance (GAA) to counter the claims of the ISA Network.

Commercial shrimp farming has displaced local communities, exacerbated conflicts, decreased the quality and quantity of drinking water and decimated the natural fish species on which the local population rely. The population of these areas ended up living right on the coast, without the benefit of their protective mangrove forests. Their coral reefs were eroded by pollution, dynamite fishing, tourists (who tread on the reefs) and the rising temperature of the sea.

Aquaculture and tourism corporations have been allowed to destroy the coastal environment of Southeast Asia because the current neoliberal trade system favors corporations over and above all concerns for the environment and the people living in it. Trade liberalization, through the World Trade Organization (WTO), has enabled corporations to challenge the legislation of the countries they wanted to operate in, legislation that was designed to protect the local environment.

Ecological and human disasters such as the 2004 tsunami will continue to occur as long as the current Global Economic System is allowed to exist in its present form.

|

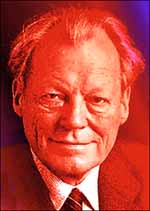

| Former German Chancellor Willy Brandt |

The Brandt Report Was Visionary

Way back in the 1980s, former German Chancellor Willy Brandt warned that the current global economic system, with its emphasis on profit at all costs, would lead to environmental degradation and worsening poverty in the Third World. He said "Important harm to the environment and depletion of scarce resources is occurring in every region of the world, damaging soil, sea and air. The biosphere is our common heritage and must be preserved by cooperation -- otherwise life itself could be threatened" (North South, 72 -73.) How prophetic these words sound today.

He set up the Independent Commission on International Development Issues to make an in-depth study of the global economy. His team of advisers included many experts in the field of international policy and economics. Their detailed report came to the conclusion that the developed nations dominated international trade and that this was unbalanced and biased in favor of large corporations based in the West.

The Brandt Commission was the first major independent global panel to examine connections between the environment, international trade, international economics and the Third World. The United Nations Conference on Environment and Development took Brandt's proposals regarding the environment seriously enough to hold international conferences in Rio in 1992 and in Kyoto in 1997. However, America refused to sign the Kyoto Protocol and corporate power prevented any of the Brandt Report recommendations being put into practice.

The Brandt Report called for a complete restructuring of the global economy to protect the environment and meet the needs of the world population. Willy Brandt said: "We see a world in which poverty and hunger still prevail in many huge regions; in which resources are squandered without consideration of their renewal; in which more armaments are made and sold than ever before; and where a destructive capacity has been accumulated to blow up our planet several times over." He proposed a Summit of World Leaders, with the backing of a global citizens movement, to discuss how to meet the needs of the majority of the world's people. This would, he recognized, mean reforming the international economy. He proposed a series of measures, including:

An emergency aid program to assist countries on the verge of disaster

Third World debt forgiveness

Fair trade

The stabilization of world currencies

A reduction in the arms trade

Global responsibility for the environment

A major overhaul of the global economic system.

Brandt also recognized that poverty contributes to high birthrates and that overpopulation puts pressure on the environment. This has indeed happened all over the world, including Southeast Asia. Brandt also called for coordinated relief programmes for areas where disasters had already occurred.

A Prophesy Deferred

Two decades later, world leaders had not responded to any of Brandt's proposals in any meaningful way. They continued to allow an ever-increasing export of arms to some of the most repressive regimes, and public apathy towards the plight of the world's hungry billions continued.

In the 1980s Brandt was calling for preventive action and his proposals were falling on deaf ears. Only now is preventive action beginning to be taken seriously. The World Bank estimates that losses caused by [natural] disasters in the 1990s could have been cut by $280 billion if $40 billion had been spent on preventive measures. Whether protection of the environment came into the equation is not clear but surely the preservation of the coastal environment of Southeast Asia was more important than providing a luxury item of food to the US, Europe and Japan.

Only one organization has the people and the close relationships with governments to make coordinated disaster aid work, the UN's Office of Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). Yet immediately after the tsunami, world leaders were in disagreement over coordination of the relief operation. George Bush refused to cooperate with the UN because of his long-running differences with the UN leadership. World opinion eventually forced him to recognize the need for cooperation with the OCHA for the smooth running of the disaster relief.

However, the OCHA is far from perfect, partly because it has not been given the support it needs by all the member countries of the UN. Willy Brandt recognized that the UN needed to be restructured to make it democratic and effective and all the UN agencies needed to be reformed to make them more efficient. He called for emergency programs for food, housing and healthcare to be coordinated. He recommended cutting the red tape to ensure that resources reached impoverished people directly, unfiltered through inefficient bureaucracy. He called for national projects, overseen by representatives from developed and developing nations.

He recommended that instead of fighting wars, armies and navies from the developed world could be deployed to bring in the food, resources and technology needed to help poor nations reverse hunger and poverty. This has indeed been happening since the tsunami. Armies and navies have indeed been bringing food, resources and technology to the disaster areas. Ironically, as George Monbiot points out in the January 4 Guardian, the US Marines who have been sent to Sri Lanka to help the rescue operation were, just a few weeks ago, murdering the civilians, smashing the homes and evicting the entire population of the Iraqi city of Falluja.

For more information contact: