Civil Preparedness and the Sacrifice of the 'Stay-Behinds'

By Gar Smith

October 27, 2005

|

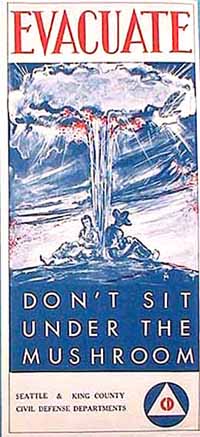

| Anyone too poor to have access to a vehicle was left stranded by the floodwaters of Hurricane Katrina. This was not an oversight. Plans to abandon the poor have been an unspoken part of emergency planning since the days of the Cold War. Credit: www.ctv.ca |

"The President's principal message to the people... was that he was ordering the movement of people from the cities." Twenty-nine days later, nuclear war erupted and the political landscape was changed forever. "There are supposed to be about 1,500 fragments of what only last year was the United States of America. There are rumors that the nation will come together again, but I think it will take a long time. There are still regions of the country which people simply avoid."

These excerpts are taken from the "diary" of a fictitious insurance salesman named Jack Shuler -- an imaginary survivor of "The Nuclear Crisis of 1979." The diary appears in a little-known Defense Civil Preparedness Agency (DCPA) report published in 1976 for distribution "to DCPA personnel (involved) in developing plans for nuclear civil protection." It was intended to be read by government planners who believed that a nuclear war was "winnable."

Twenty-nine years later, this little-noticed document provides a chilling look into the dark side of disaster management. It is clear from this study that the abandonment of the poor and elderly to the battering winds and deadly floodwaters of Hurricane Katrina was not simply the result of poor planning -- it was the fulfillment of a well-established policy that views major calamities as opportunities for "social cleansing."

Crisis Relocation Planning

In 1983, the Reagan Administration announced a $10 billion, five-year civil defense program based on the strategies spelled out in this report.

The Reagan White House and the Pentagon had claimed that Crisis Relocation Planning -- the evacuation of America's cities to "host areas" outside targeted urban centers -- could save 80 percent of the population from nuclear war. The government's actual1976 study, however, was not so optimistic.

In this chilling scenario, the DCPA envisioned a Superpower confrontation over Berlin leading to the outbreak of tactical nuclear war in Europe. In response, the US launches a limited "first strike" against the Soviet Union and, on August 6, 1979, the Soviets respond, raining 5,000 megatons of nuclear explosives onto the US.

Out of a population of 220 million Americans, only 78 million -- roughly 35 percent -- could be called survivors. The initial explosions killed 24 million Americans and left 15 million severely injured. Because 80 percent of the bombs were ground-burst weapons designed to maximize fallout, another 38 million badly irradiated survivors would die within a few months or suffer sterility, cancer, leukemia. Some 64 million less-contaminated Americans would give birth to a generation of mutants or still-borns.

|

| An example of "Strategic Racism." This government Civil Defense pamphlet from the 1950s adapts the then-popular stereotype of the "lazy Mexican sleeping under a cactus" and ads a barefoot wife and baby. The message was clear: People like this would be the first to die in a nuclear blast. Fifty years, later, FEMA was prepared to let the poor perish. |

Good Riddance to the "Stay-behinds"

While these implications were devastating, they were not the main concern of the DCPA report. The author of "The Nuclear Crisis of 1979," William M. Brown, was engaged in an exercise to determine what it would take to make Crisis Relocation Planning (CRP) work. CRP was a Reagan-era plan for the mass-evacuation of US cities in advance of a possible Soviet missile strike. According to Brown's report, it was believed that Crisis Relocation Planning would save "about 100 million lives" -- although one in every four of those survivors would be dying, slowly, from radiation-induced illness.

In his fictitious scenario, Brown presents an optimistic scenario where previously heedless Americans respond to the government's call and become obsessed with nuclear survival. From that moment on, "it was CD at home, CD at work, CD on the news... every institution became involved in civil defense: every school, church, business, social club, community and government agency."

In his daily record of post-attack America, Brown's alter ego, Jack Shuler reports that things went well for the imaginary Americans who endured the Nuclear Crisis. "Perhaps the most surprising result of the planned evacuation was how well it worked," Shuler wrote. "In many cases, traffic moved out 50 to 75 percent faster than planned." But the highways to haven didn't offer salvation to everyone. As Shuler's diary explains: "There were some 'unthinkable' consequences of nuclear war that might please the dark side of certain conservative ethics with little sympathy for the pacifists, the anti-war groups, the fatalists."

Quoting from an article in an imaginary newspaper, Shuler addresses the question of the "Stay-Behinds" -- the people who will remain in the doomed cities even though they know they are targeted for destruction. The list of expendable humanity included:- "Bowery winos and heroin addicts are obvious groups. Of the nation's alcoholics, estimated at about 9 million adults, we would expect some to stay

. Those 'further gone' would tend to remain behind."

- "Anti-war idealists... to them, an evacuation should be protested."

- "Older residents without families...."

- "Individuals, perhaps those from minority communities who might not be willing to tolerate the cultural shock of relocation to a 'strange environment' in which they believe they would feel lonely and unwanted."

- "Pet lovers who will not leave behind their dogs, cats, birds, snakes, horses or ocelots."

In his diary, Shuler voices his personal reaction to the Stay-Behinds:

"The task of moving and holding a substantial number of recalcitrants was repugnant. There would be plenty to do without having to drag along perhaps 10 to 20 percent of the population, many of whom are screaming or foot-dragging protestors, and who may possibly include some saboteurs of the CRP."

In his diary, Shuler describes his personal CRP experience in a series of efficient, well-orchestrated stages involving Moving Out and the Arrival of his Shelter Group. The Shuler family is given a large basement in a two-story house. In their new home, they find that "doctors, dentists, laundries were open at least 16 hours a day" and all the activities involved in "the billeting, housing, organization and sheltering of the relocated population" were available and functioning smoothly.

Two Outcomes -- Peace and a Troubled Return

Once America's cities have been successfully evacuated and the populations relocated to temporary homes hundreds of miles away, the DCPA scenario considers the two opposite conclusions to the Crisis.

In the first scenario, peace is negotiated before a single strategic missile is launched. America breathes a sigh of relief and, as one diary excerpt puts it: "The world once more was transformed, into a beautiful place in which to live" -- except, of course, for the "the fatalities, the injuries, the damage to property and the radioactivity from the tactical nuclear weapons used in Europe." (It is revealing that the DCPA's author dismisses the plight of the Europeans and equates the "world" with the US.)

Unfortunately, even in the US, there were some problems. Jack Shuler describes one unforeseen dilemma that arises following the peaceful resolution of the crisis:

"No agency, federal or regional, had made adequate going-home plans." As a result, "adjustments" were "awkward." Retail stores needed more time to get into operation and there was a gasoline shortage. People wondered about whether they had to pay back rents, what business contracts to honor. The securities market had collapsed but the rich had bought up most of the property "so the poor were poorer and perhaps a third of the people were, in fact, bankrupt."

As for the once-thriving urban centers, they had lost their attraction. Now recognized as strategic "targets," they are abandoned forever to the "derelicts -- those who took their chances with alcohol, drugs, crime and nuclear threats" (the last apparently a veiled reference to anti-nuclear protestors).

Nuclear Attacks and the Post-War Recovery

Without these social "derelicts" to worry about, the DCPA scenario moves on to envision the consequences of a massive nuclear attack on America's target cities and provides a number of surprisingly optimistic visions of Post-Attack Survival.

With most of the civilian population successfully relocated, it is assumed that "paramedics" would be able to handle "perhaps 80 to 90 percent of the medical cases normally handled by MDs." The DCPA also concluded that "most of the telephones were expected to keep working" as well as "at least one radio station and one TV station," that "nearby electric power plants were expected to continue functioning with stockpiles of fuel ample... for several months."

Despite the deaths of millions of Americans and unparalleled destruction of infrastructure, the DCPA envisioned a brief two-to-four-week Early Survival period followed closely by a brisk Economic Reorganization campaign. The Reorganization would be lead by "industrial and commercial teams, which become effective in making physical preparations to enhance the survival and recovery prospects. The success of these efforts during the crisis improves morale."

But not even corporate powerhouses like Bechtel and Halliburton could be expected to tackle recovery efforts beyond the perimeters of a few select CRP sites. Any outlying pockets of post-war survivors would be on their own "as the survival of the federal and most state governments would be in doubt" and any surviving bureaucrats "might be as useful as musicians after an earthquake."

The Aftermath Society: "A Temporary Dictatorship"

The "Nuclear Crisis of 1979" portrays an Aftermath Society fretting over such matters as clarification of property rights, distribution of surviving resources, creating "a stable valuable currency," organizing "economic investments," and determining the future of "the private sector."

After the Apocalypse, "more of these important functions seemed to be susceptible to quick solution by a post-attack government except through the crudest kind of authoritarianism such as the use of martial law or a temporary dictatorship."

The best recourse, wrote one "survivor," would be to "advise the community to become as independent as possible, especially of any dependence upon timely post-attack actions by the federal government and to hope for the best."

One of the first tasks the survivors would face would be the clean-up.

"Before a post-attack recovery effort could be launched," the DCPA report indicated, "the town would have to be decontaminated." This could be accomplished with "about 6 hours of labor from every able-bodied adult. Some would use mechanical equipment for street cleaning; others would use hoses to wash down hard surfaces; some would sweep, some would clean roofs, gutters and sills."

Still others would pick up spades to turn over topsoil "thereby burying surface particles under several inches or more of earth cover." With amazing optimism, the report promises that this would lower radiation "by as much as 95 percent."

Of course, some relocation areas would remain so "hot" from fallout, that refugees would be forced to flee to cooler ground. This could create problems.

"The influx of so many refugees from these hot spot areas might be strongly resented in the less-affected host areas and perhaps even prohibited," the DCPA planner predicts.

"When the illusion of the impossibility or unthinkability of a nuclear attack is broken, the sudden rude awakening may lead to temporary panicky reactions," Brown concluded. But, with good government planning, the relocated citizenry will develop "a high morale, to the point where the business-as-usual attitude in commercial firms becomes rapidly transformed into one which emphasizes cooperation for survival."

Eventually, Brown predicts, a new social order could evolve based on cooperation rather than competition. "The profit motive may be best in peacetime commerce," Brown concedes, "but in a short nuclear emergency, other values can overwhelm it."

The Crisis Relocation Plan was eventually dropped when military strategists pointed out that it could actually help trigger a nuclear war. If the US were to order the mass evacuation of its cities, critics pointed out, the Russians might see this as a provocation -- i.e., a first-step towards preparing for a nuclear attack. Rather than waiting for the US to gain the strategic advantage by minimizing the vulnerability of its cities, the Russians (whose civilian populations were still in place and at risk) might be tempted to accelerate plans for attack.

In the 1953 movie version of "War of the Worlds," the military and civilian leadership is seen making plans as the Martians close in on Los Angeles. The following dialogue takes place: "Most people have already left the City." "The Red Cross is standing by. We have mobilized emergency vehicles." The next scene shows car-less residents boarding rows of commandeered public buses and scores of ill and elderly patients being carefully removed from hospitals.

Hollywood had a better evacuation plan 52 years ago. One reason is that somewhere between "The War of the Worlds" and "The Nuclear Crisis of 1979," the government began to "think the unthinkable": It began to look upon millions of citizens as inconsequential and disposable -- individuals not worth saving.

The failure to prepare for the evacuation of New Orleans' poor and disadvantaged was not just a failure of planning, it was a manifestation of a greater failing -- the failure of the United States of America to honor its founding pledge to protect "life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness" for every member of the Republic.

For more information contact: