Thanksgiving: A National Day of Mourning

George W. Bush Pardons a Turkey

Turkeys, Pardons and Frying Pan Park

December 16, 2006

While the Thanksgiving holiday is a national day of rejoicing for some Americans, it remains a national day of mourning for others. Thanksgiving as presently celebrated -- that is, as a national political event -- is both a fable and an affront to civilized values.

When the Commonwealth of Massachusetts held its annual Thanksgiving feast at Plymouth in 1970, it invited Frank James (an elder known to the Wampanoag People as Wamsutta) to speak at the celebration.

When the text of Mr. James' speech became known, the Commonwealth chose to "disinvite" him. Wamsutta refused to allow the modern Pilgrims to revise his speech, which powerfully addressed the history of oppression inflicted on Native Americans by the Pilgrims.

Wamsutta (1923-2001) left the dinner ceremonies and went to the hill near the statue of Massasoit, the great Wampanoag leader. Overlooking the replica of the Mayflower anchored in Plymouth Harbor, he gave the speech that he would have given to the descendents of the Pilgrims and their guests. A small crowd of Native Americans and supporters listened as Wamsutta talked about the takeover of the Wampanoag tradition, culture, religion, and land.

The silencing of this strong-and-honest voice inspired the Native American community to recognize "Thanksgiving Day" as an annual "National Day of Mourning."

Here is the text of Wamsutta's 1970 speech.

Thanksgiving: A National Day of Mourning

Wamsutta

|

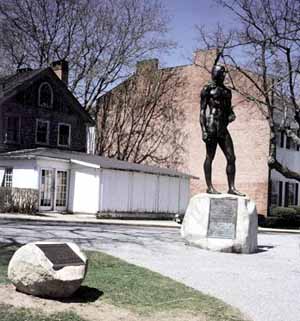

| Day of Mourning Plaque and Massasoit Statue on Cole's Hill in Plymouth, Massachusetts. Credit: United Native Americans of New England |

Ispeak to you as a man -- a Wampanoag Man. If I am a proud man, it is because I am proud of my ancestry, and proud of my accomplishments, won by a strict parental direction. They said: "You must succeed, for your face is a different color, in this small Cape Cod community!"

I am a product of two socioeconomic diseases: poverty and discrimination. I, and my brothers and sisters, have painfully overcome them, and to some extent, we have earned the respect of our Cape Cod community. We are Indians first but we are termed "good citizens." Sometimes we are arrogant but only because society has pressured us to mask our pain by being so.

It is with mixed emotions that I stand here to share my thoughts. Thanksgiving is a time of celebration for those of you who celebrate another anniversary of the beginning for the white man in America. It is a time of looking back, of reflection. And it is with a heavy heart that I look back upon what happened to my Wampanoag People.

Even before the Pilgrims landed, it was common practice for European explorers to capture Indians, take them to Europe, and sell them as slaves for 220 shillings apiece. The Pilgrims themselves had hardly explored the shores of Cape Cod for four days before they had robbed the graves of my ancestors and stolen their corn and beans.

Massasoit, the great Sachem [i.e., leader] of the Wampanoag, knew these facts, yet he and his People welcomed and befriended the settlers of the Plymouth Plantation. Perhaps he did this because his Tribe had been depleted by an epidemic. Or his foreknowledge of the harsh oncoming winter was the reason for his peaceful acceptance of these facts. In any case, this action by Massasoit was perhaps our biggest mistake.

We, the Wampanoag, welcomed you, the white man, with open arms, little knowing that it was the beginning of the end -- that before 50 years were to pass, the Wampanoag would no longer be a free people.

The Destruction of the Wampanoag People

What happened in those short 50 years from 1621-1671? What has happened in the last 349 years (1621-1970)? History gives us the facts: from the very first contact, there were atrocities; there were broken promises; and most of these centered around land ownership. Among ourselves, we understood that there were boundaries, but never before did we have to deal with fences and stone walls.

The white man had a need to prove his worth by the amount of land that he owned. Only ten years later, when the Puritans came, they treated the Wampanoag with even less kindness in converting the souls of the so-called "savages." Although the Puritans were harsh to members of their own society, they pressed the Indian between stone slabs and hanged us as quickly as any other "witch."

And so, down through the years, there is record after record of Indian lands being taken and, in token, reservations being set up for him upon which to live. The Indian, having been stripped of his power, could only stand by and watch while the white man took his land and used it for his personal gain. The Indian could not understand this; to him, land was for survival, to farm, to hunt, to be enjoyed. It was not to be abused.

Historically, we see incident after incident where the white man sought to tame the "savage" and convert him to the Christian ways of life. The early Pilgrim settlers led the Indian to believe that if he did not behave, they would dig up the ground and unleash the great epidemic again [when the explorers had given us blankets that carried smallpox].

The white man used the Indian's nautical skills and abilities. They let him be only a seaman but never a captain. Time and time again, in the white man's society, we Indians have been termed the "low man on the totem pole."

Has the Wampanoag really disappeared? On this question, there is still an aura of mystery. We know there was an epidemic that took many Indian lives; but some Wampanoags moved west and joined the Cherokee and Cheyenne. They were forced to move. Some even went north to Canada! Many Wampanoag put aside their Indian heritage and accepted the white man's way for their own survival. Today, there are some Wampanoag who do not wish it known they are Indian for social or economic reasons.

What happened to those Wampanoags who chose to remain and live among the early settlers? What kind of existence did they live as "civilized" people? True, living then was not as complex as life today, but they dealt with the confusion and the change. Honesty, trust, concern, pride, and politics wove themselves in and out of the Wampanoags' daily living. Hence, they were mischaracterized as crafty, cunning, rapacious, and dirty.

History wants us to believe that the Indian was a savage, illiterate, uncivilized animal. On the one hand, that history that was written by an organized and disciplined people, to "expose" us as an unorganized and undisciplined entity.

On the other hand, two distinctly different cultures met. One thought they must control life; the other believed life was to be enjoyed, because nature decreed it. Let us remember that the Indian is now, and always was, just as human as the white man. The Indian feels pain, gets hurt and becomes defensive, has dreams, bears tragedy and failure, suffers from loneliness, needs to cry as well as laugh. He, too, is often misunderstood.

The white man in the presence of the Indian is still mystified by his uncanny ability to make him feel uncomfortable. This "savageness" may be the image the white man has created of the Indian; this image has boomeranged because people know it isn't a mystery; it is fear; fear of the Indian's truthful temperament!

The Resurrection of the Wampanoag

High on a hill, overlooking the famed Plymouth Rock, stands the statue of Massasoit, our great Sachem. Massasoit has stood there many years in silence. We, the descendants of this great Sachem, have been a silent people. The necessity of making a living in this materialistic society of the white man has made us silent. Today, I and many of my people are choosing to face the truth: we ARE Indians; we ARE the Wampanoag People!

Although time has drained our culture, and our language is almost extinct, we who are the Wampanoags still walk the lands of Massachusetts. We may be fragmented, we may be confused. Many years have passed since we have been a people together. Our lands were invaded. We fought as hard to keep our land as you, the whites, did to take our land away from us. We were conquered, we became the American prisoners of war in many cases, and wards of the United States Government, until only recently.

And yet our spirit refuses to die. Yesterday we walked the woodland paths and sandy trails. Today we must walk the macadam highways and roads. We are uniting. We are standing, not in our wigwams, but in your concrete tent. We stand tall and proud. And before too many moons pass, we will right the wrongs we have allowed to happen to us.

We forfeited our country. Our lands have fallen into the hands of the aggressor. We have allowed the white man to keep us on our knees. What has happened cannot be changed. But today we must work towards a more humane America, a more INDIAN America: an America where people and nature once again are important; an America where the Indian values of honor, truth, and universal brotherhood prevail.

You, the white man, are celebrating an anniversary. We, the Wampanoags, will help you celebrate, but only in the concept of another beginning. It WAS the beginning of a new life for the Pilgrims. Now, 350 years later, it IS the beginning of a new determination for the original American: the American Indian.

For more information, contact: United Native Americans of New England (UAINE), 284 Amory St., Jamaica Plain, MA 02130. (617) 232-5135. www.unaine.org. info@uaine.org

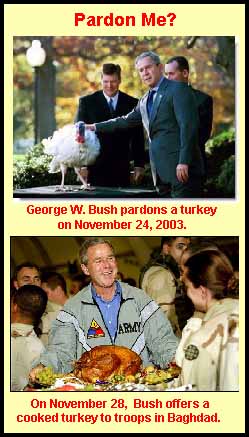

George W. Bush Pardons a Turkey

The Rose Garden / Thanksgiving 2006

|

| White House Photo: Susan Sterner. AP photo: Pablo Monsivals |

GEORGE W. BUSH: Good morning. Thanks for coming.... Tomorrow is our day of Thanksgiving. It's a national observance first proclaimed by George Washington. In our journey across the centuries from a few tiny settlements to a prosperous and powerful nation, Americans have always been a grateful people. We're grateful for our beautiful land. We're grateful for a harvest big enough to feed us all, plus much of the world. We're grateful for our freedom. We're grateful for our families. And we're grateful for life itself....

We're a generous country. We're filled with caring citizens who reach out to others, people who've heard the universal call to love a neighbor as we want to be loved ourselves. On Thanksgiving and every day of the year, Americans live out of a spirit of compassion and care, and I thank you for that....

The name of the national Thanksgiving turkey has been chosen by online voting at the White House website. By the decision of the voters, this turkey is going to be called Flyer. And there's always a backup bird, just in case the guest of honor can't perform his duties, and the backup bird's name is Fryer. Probably better to be called Flyer than Fryer....

What You Can Do: Want to have a lark at the expense of a lame duck? The-Edge suggests a national grassroots campaign to name the 2007 Thanksgiving turkey. The name we are placing in nomination for the lucky gobbler is... "George Dubya."

Turkeys, Pardons and Frying Pan Park

Arundhati Roy

The tradition of �turkey pardoning� in the US is a wonderful allegory for New Racism. Every year, the National Turkey Federation presents the US president with a turkey for Thanksgiving. Every year, in a show of ceremonial magnanimity, the president spares that particular bird (and eats another one).

After receiving the presidential pardon, the Chosen One is sent to Frying Pan Park in Virginia to live out its natural life -- while the rest of the 50 million turkeys raised for Thanksgiving are slaughtered and eaten.

That's how New Racism in the corporate era works. A few carefully bred turkeys -- the local elites of various countries, a community of wealthy immigrants, investment bankers, the occasional Colin Powell, or Condoleezza Rice, some singers, some writers (like myself) -- are given absolution and a pass to Frying Pan Park.

The remaining millions lose their jobs, are evicted from their homes, have their water and electricity connections cut, and die of AIDS. Basically, they're for the pot.

But the fortunate fowls in Frying Pan Park are doing fine. Some of them even serve as board members on the Turkey Choosing Committee -- so who can say that turkeys are against Thanksgiving? They participate in it! Who can say the poor are anti-corporate globalization? There's a stampede to get into Frying Pan Park. So what if most perish on the way?

Indian author and activist Arundhati Roy is the winner of the 1997 Booker Prize for literature. Excerpted from a speech at the opening plenary of the World Social Forum in Mumbai. India, on January 16, 2004.

For more information contact: