Deforestation: The Hidden Cause of Global Warming

Uganda Wants Industrialized Nations To Pay for Climate Change

June 13, 2007

Deforestation:

The Hidden Cause of Global Warming

by Daniel Howden / The Independent

|

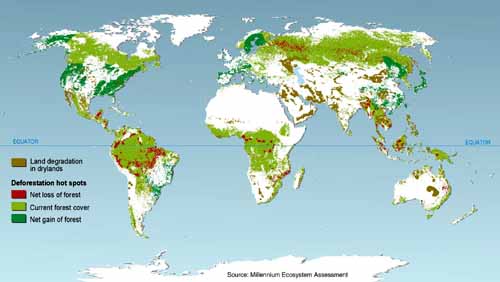

| In 2003, two billion tons of CO2 entered the atmosphere from the deforestation of 50 million acres -- an area of felled forests the size of England, Wales and Scotland. Credit: Map: Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. |

In the next 24 hours, deforestation will release as much CO2 into the atmosphere as 8 million people flying from London to New York. Stopping the loggers is the fastest and cheapest solution to climate change. So why are global leaders turning a blind eye to this crisis?

The accelerating destruction of the rainforests that form a precious cooling band around the Earth's equator, is now being recognized as one of the main causes of climate change. Carbon emissions from deforestation far outstrip damage caused by planes and automobiles and factories.

The rampant slashing and burning of tropical forests is second only to the energy sector as a source of greenhouses gases according to report published today by the Oxford-based Global Canopy Program, an alliance of leading rainforest scientists.

Figures from the GCP, summarizing the latest findings from the United Nations, and building on estimates contained in the Stern Report, show deforestation accounts for up to 25 percent of global emissions of heat-trapping gases, while transport and industry account for 14 percent each; and aviation makes up only 3 percent of the total.

"Tropical forests are the elephant in the living room of climate change," said Andrew Mitchell, the head of the GCP.

Scientists say one days' deforestation is equivalent to the carbon footprint of eight million people flying to New York. Reducing those catastrophic emissions can be achieved most quickly and most cheaply by halting the destruction in Brazil, Indonesia, the Congo and elsewhere.

No new technology is needed, says the GCP, just the political will and a system of enforcement and incentives that makes the trees worth more to governments and individuals standing than felled. "The focus on technological fixes for the emissions of rich nations while giving no incentive to poorer nations to stop burning the standing forest means we are putting the cart before the horse," said Mr. Mitchell.

Most people think of forests only in terms of the CO2 they absorb. The rainforests of the Amazon, the Congo basin and Indonesia are thought of as the lungs of the planet. But the destruction of those forests will in the next four years alone, in the words of Sir Nicholas Stern, pump more CO2 into the atmosphere than every flight in the history of aviation to at least 2025.

Indonesia became the third-largest emitter of greenhouse gases in the world last week. Following close behind is Brazil. Neither nation has heavy industry on a comparable scale with the EU, India or Russia and yet they comfortably outstrip all other countries, except the United States and China.

What both countries do have in common is tropical forest that is being cut and burned with staggering swiftness. Smoke stacks visible from space climb into the sky above both countries, while satellite images capture similar destruction from the Congo basin, across the Democratic Republic of Congo, the Central African Republic and the Republic of Congo.

According to the latest audited figures from 2003, two billion tons of CO2 enters the atmosphere every year from deforestation. That destruction amounts to 50 million acres -- or an area the size of England, Wales and Scotland felled annually.

The remaining standing forest is calculated to contain 1,000 billion tons of carbon, or double what is already in the atmosphere. As the GCP's report concludes: "If we lose forests, we lose the fight against climate change."

Standing forest was not included in the original Kyoto protocols and stands outside the carbon markets that the report from the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) pointed to this month as the best hope for halting catastrophic warming.

The landmark Stern Report last year, and the influential McKinsey Report in January agreed that forests offer the "single largest opportunity for cost-effective and immediate reductions of carbon emissions".

International demand has driven intensive agriculture, logging and ranching that has proved an inexorable force for deforestation; conservation has been no match for commerce. The leading rainforest scientists are now calling for the immediate inclusion of standing forests in internationally regulated carbon markets that could provide cash incentives to halt this disastrous process.

Forestry experts and policy makers have been meeting in Bonn, Germany, this week to try to put deforestation on top of the agenda for the UN climate summit in Bali, Indonesia, this year. Papua New Guinea, among the world's poorest nations, last year declared it would have no choice but to continue deforestation unless it was given financial incentives to do otherwise.

Richer nations already recognise the value of uncultivated land. The EU offers EUR200 (£ 135) per hectare subsidies for "environmental services" to its farmers to leave their land unused.

And yet there is no agreement on placing a value on the vastly more valuable land in developing countries. More than 50 percent of the life on Earth is in tropical forests, which cover less than 7 percent of the planet's surface.

They generate the bulk of rainfall worldwide and act as a thermostat for the Earth. Forests are also home to 1.6 billion of the world's poorest people who rely on them for subsistence. However, forest experts say governments continue to pursue science fiction solutions to the coming climate catastrophe, preferring bio-fuel subsidies, carbon capture schemes and next-generation power stations.

Putting a price on the carbon these vital forests contain is the only way to slow their destruction. Hylton Philipson, a trustee of Rainforest Concern, explained: "In a world where we are witnessing a mounting clash between food security, energy security and environmental security -- while there's money to be made from food and energy and no income to be derived from the standing forest, it's obvious that the forest will take the hit."

news.independent.co.uk/environment/climate_change/article2539349.ece

Posted in accordance with Title 17, US Code, for noncommercial, educational purposes.

Uganda Wants Industrialized Nations

To Pay for Climate Change

The Economist (May 23, 2007)

|

| Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni. |

At a recent African Union summit, Uganda's combustible president, Yoweri Museveni, declared climate change an act of aggression by the rich world against the poor one -- and demanded compensation. The moral arguments on climate change are even murkier than arguments about other wrongs done to Africa, such as slavery, but Museveni may have hit on something.

If the predictions of the UN's Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) hold true, climate change may have a graver effect on Africa than on any other continent. Scientists now blame industrialization (the rich world) for some of the warming. In any event, the contrast between poverty in Africa and carbon gluttony elsewhere is sharp. Why should the poorest die for the continued excesses of the richest?

The IPCC's most recent regional report predicts a minimum 2.5°C increase in temperature in Africa by 2030; drylands bordering the deserts may get drier, wetlands bordering the rainforests may get wetter. The panel suggests the supply of food in Africa will be "severely compromised" by climate change, with crop yields collapsing in some countries.

In the drylands, water may become a critical issue. Soaring temperatures and erratic rainfall may dry up surface water. Between 75 million and 250 million Africans, out of the 800 million or so now living in sub-Saharan Africa, may be short of water. The soil will hold less moisture, bore-holes will become contaminated, and women and girls will have to walk ever greater distances to fetch water. Vegetative cover will recede. The IPCC guesses that 600,000 square kilometers (232,000 square miles) of cultivable land may be ruined.

Warming may also hurt animal habitats and biodiversity. More algae in freshwater lakes will hit fishing. The glaciers of Uganda's Rwenzori mountains, of Tanzania's Kilimanjaro and of Kenya's eponymous mountain may disappear; only seven of the 18 glaciers recorded on Mt. Kenya in 1900 still remain. At the same time, a likely rise in sea levels may threaten the coastal infrastructure of northern Egypt, the Gambia, the Gulf of Guinea and Senegal.

There are two caveats to this gloomy scenario. The first is that some parts of Africa may benefit from climate change. Increased rainfall in highland areas in eastern Africa could, for example, be beneficial. Second, though climate-change models have improved, they have been unreliable in Africa. The broad outline is plain but the detail is guesswork.

Still, some scientists think that climate change may be even crueller to parts of Africa than the IPCC predicts. The important point, they say, is not the degree of warming but the continent's vulnerability to it. A University of Pretoria study estimates that Africa might lose $25 billion in crop failure due to rising temperatures and another $4 billion from less rain. The already impoverished drylands would suffer most. Some cite the war in Sudan's Darfur region as proof of the damage done by climate change, soil erosion and overpopulation.

Unfortunately, few African leaders have grasped the scale of the challenge posed by climate change. Most oil-producers have squandered their bonanza. Nigeria has failed to plan for how to stem the dreadful pollution in its oil-producing Delta region or to prevent desertification tearing at the fabric of its dry Muslim north. South Africa is only just beginning to own up to its coal addiction.

Uganda's Museveni is fighting off a rare insurrection from his supporters against plans to turn a piece of Ugandan rainforest over to farming. The World Meteorological Organisation says that weather-data collection in Africa has recently got worse, just as the need for accurate figures has grown; many of the automatic weather stations it helped set up have fallen into disrepair.

The AU has done little to sound the climate-change alarm. Kenya's president, Mwai Kibaki, says that Africa should "join hands" with its friends in the rich world over climate change. He wants more carbon-trading projects to come to Africa; so far, most have gone to Asia.

His advisers admit that Mr. Kibaki's ambitious plan to turn Kenya into an industrial country by 2020 worries environmentalists, but say that reforestation, thermal power and better management of water and grazing would, if they materialized, offset the damage.

www.newvision.co.ug/D/8/459/566734

Posted in accordance with Title 17, US Code, for noncommercial, educational purposes.

For more information contact: