Turkey's Environment: Battered but Looking Better

By Gar Smith / The Edge

December 22, 2007

|

| The Bosphorus looks wide and inviting but the twists and turns that lurk on this famous stretch of water regularly lead to ship colisions -- and when oil tankers are involved, the results can prove deadly and calamitous. Photos by Gar Smith |

Turkey's Environment Minister Fevzi Aytekin once observed that his country has "a unique geographic and geopolitical situation -- a junction of old civilizations and beautiful nature." There are approximately 12,000 species of flora in Europe and 75% can be found in Turkey. Turkey's first Environmental Law was enacted in 1983, the country created a Ministry of the Environment in 1991, and in 2007, the Ministry of Environment and Forestry compiled Turkey's first greenhouse gas inventory.

Nonetheless, the European Union's 2000 report card on Turkey gave the country low marks on air and water quality, waste management, industrial pollution, and conservation.

Despite its vastness, spreading urbanization threatens to erode the country's open spaces. South of Istanbul, where a valley of sunflowers spills to the horizon, the beauty of the scene in marred by a large billboard that reads: "Endustrial Muftak." The valley has been offered for sale to industrial developers.

Price Waterhouse Cooper has rated Istanbul as the fastest-changing city in the world with $3.5 billion in foreign investments fueling construction of highrises, apartments, shopping malls and commercial buildings. "The temple of capitalism spread to the provinces," as the Financial Times put it.

Under pressure to join the EU, Turkey is trying to spiff up its environmental laws. Turkey joined the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change in 2004. Turkey is a party to the CITES and RAMSAR treaties but has not yet signed the Kyoto Protocol. In 2004, the World Bank offered Turkey 150 billion Euro for "green energy" projects.

Each year, heavy winter rains flush tons of silt downstream, a problem compounded by the clearcutting of oak and pine forests. In fairness to modern Turks, the problem of forest loss and soil erosion has plagued Turkey since the days of the prehistoric Hittite civilization and lead the Romans to abandon several important port cities, including Ephesus. Turkey has embarked on an ambitious 20-year reforestation program to save the country's topsoil.

There is little of the litter that marks most US cities and roadsides -- with one exception. At most tourist stops, the ground just beyond the walls that define the "vista points" is frequently cluttered with plastic water bottles once filled with dogal kaynak soyu (natural spring water) bearing brand names like Baykal, S'eker Su. Erikli Zirveden. Pamla Isoanaica Damla) and Biota Colorado Pure Spring Water (in a "PLAnet Friendly" bottle).

Many of Turkey's major environmental problems involve water. Each year, more than 45,000 vessels traverse the narrow Bosporus Straits and 10% are tankers loaded with oil. Ship traffic is expected to grow 40% in the years ahead. There are 12 sharp turns along the 19-mile channel, which explains why the straits average more than 3 collisions per month. In 1979, one ship collision killed 43 people and dumped 95,000 tons of oil into the water -- 2.5 times the size of the Exxon Valdez spill in Alaska.

In 1994, a Greek Cypriot tanker hit another vessel, killing 30 crewmembers and spilling 20,000 tons of oil, which caught fire and burned for five days. Turkey passed new regulations to monitor oil tankers in the Straits but, in 1999, a Russian oil tanker split in two near Istanbul, coating the Marmara coast and a five-square-mile patch of ocean.

Turkey's Dams

Turkey's mountains and 26 river zones host nearly 150 hydroelectric dams and as many as 436 new dams are planned to be built by 2010. If they are all built, Turkey (which now derives 40% of its electricity from dams) could be generating 69,051 megawatt-hours of renewable hydropower per year.

While this is good news for Turkey, it's bad news for the people living downstream, especially as climate change elevates temperatures and lower waterflows around the region.

The $1.6 billion Ilusu hydropower dam on the Tigris (part of the Southeast Anatolia Project), would displace 20,000 people, destroying 52 Kurdish villages, 15 towns, and the city of Hasankeyf, an ancient archeological treasure. Moreover, the dam would reduce the flow of water to Iraq and Syria. Kerim Yildiz of the Kurdish Human Rights Project claims the dam would violate a law requiring downstream countries to give permission before such dams can be built.

The Ilisu Dam Campaign warns that the dam could degrade downstream water because wastes from Diyarbakir and other cities currently pour into the Tigris untreated. (Adding to the problem, in 1996, Greenpeace Turkey revealed that Shell Oil had pumped 487.5 million barrels of chemically polluted waste into Diyarbakir's Midyat aquafer between 1973 and 1994.)

An estimated 75% of industrial waste is discharged, untreated, into the environment while only 12% of Turkey's dwellings are connected to sewage treatment. Rusting barrels of industrial toxic wastes are frequently discovered in Istanbul neighborhoods. One neighborhood, Dilolvasi, was declared a "medical disaster area" with cancer deaths running three times higher than the world average. Under pressure to join the EU, Ankara has adopted the "polluter pays" principle, jacking up fines from a mere 4500 euros to a respectable1.5 million.

Turkey is now the world's leading dam-builder, out-pacing China in number (if not in scale) of dam projects. New baraj (dams) are under construction across Turkey but, due to the nature of the country's unstable soil, erosion will inevitably silt in the reservoirs, reducing the dams efficiency.

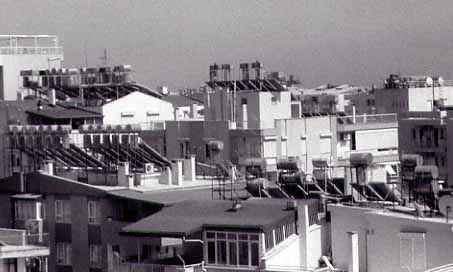

|

| Rooftop heaters are omnipresent throughout much of Turkey. Millions of simple, cheap solar-tank heaters turn sunshine into clean energy for homes and offices. |

Turkey's Energy Balance

Turkey is still heavily dependent on imported oil. One of the world's fastest-growing energy markets for the past 20 years, Turkey imports more than half of its energy (mostly from Russia) and is involved in the construction of two costly multinational oil and gas pipelines -- the Trans-Caspian and the Baku-Ceyhan. A third, "Blue Stream" pipeline would bring in cleaner-burning natural gas from Russia to replace dirty, high-sulfur Turkish coal. Turkey's wants to turn Ceyhan into a major petrochemical hub.

Coal accounts for 24% of Turkey's energy while 14.4% comes from renewable resources. Air pollution is a looming environmental concern in Turkey and the leading contributor is the energy sector, which remains heavily reliant on the burning of low quality, high-sulfur lignite.

Turkish energy use has more than tripled since the 1980s and carbon emissions have more than doubled, reaching 211 million metric tons by 2000. With CO2 emissions climbing nearly 6% per year, Turkey's spawn of Greenhouse gases could reach 871 million t/year by 2025. According to 2003 estimates, 36% of Turkey's CO2 emissions came from energy production and 34% from industry. By 2020, energy production could be producing 40% of the country's CO2. Nonetheless, Turkey "still has the lowest energy-related CO2 emissions per capita and energy consumption per capita among IEA countries."

Since 1992, Turkey's energy consumption has increased by more than 24%, growing five-times fasted than energy use in the US. In 2004, Turkey was officially admitted into the ranks of the "advanced developing countries" when its greenhouse gas emissions topped 300 million tons.

Solar Tanks Crown the Skylines

Istanbul's skyline is adorned with minarets and domes of mosques, large and small. But on closer inspection, there is something else that is remarkable about the Istanbul skyline -- the rooftops are festooned with thousands of satellite dishes and solar hot-water tanks. There are two satellite dishes for every TV set. One dish faces the Turkish broadcast satellite; the other is tilted toward the orbiting transmitter that broadcast European content.

These solar heating panels are ubiquitous. From the northern routes to Ankara, along the Silk Road to Capadocia, skirting the Meditarranean on the south and up the western coast to Troy, Gallipoli and back to Istanbul, every rooftop -- from hovels to highrises -- seems to be topped by an array of solar panels linked to a hot-water tank.

You don't need a compass to know what direction your headed in Turkey. Just look at the rooftop panels -- all facing south. Much of the built landscape constitutes a solar compass. There's magnetic north and there's solar south.

The number of solar collectors produced in 2004 alone would collectively cover 8 million square meters. These devices are far from glamorous (certainly not as solar-chic as sleek power-generating PVC panels) but they are rugged, simple and efficient. It speaks well for California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger that his call for a "million solar roofs" now also includes $25 million in rebates for the installation of 200,000 of sun-stoked hot water tanks. (NorCal Solar sets the costs of these units as between $5,500 and $6,500. One way to lower purchase costs and jump-start the program might be to order units from factories in Turkey.)

The Turkish sunbelt soaks up an annual average of 3.6 kWh/m2-day but the government has no programs to promote photovoltaic panels -- although there are at least 30,000 residential areas in the country that would find rooftop solar electricity cheaper than electricity from powerlines.

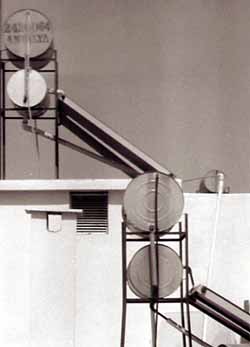

|

| A close up of a solar water tank system on the roof of a swank hotel in Antalya on Turkey's southern coast, shows the simplicity of the technology. |

Windpower in Turkey

"The wind blows money to Troy." The ancient city (nine levels of it) sat at the mouth of the Dardenells, the gateway to the Sea of Marmara, the Bosporus and the Black Sea. But because of the strong winds spilling out of the gate of the Dardanelles, it was sometimes difficult for ships to sail north. Instead, they would be blown back to Troy where ship owners would be forced to pay Troy while their ships were tied up awaiting more favorable winds.

These days, that phrase has a new meaning. Windfarms are springing up on the ridges along the Hellispont. [More in for on windturbines needed.] Other windmills pop up on the hillsides between Troy and Istanbul. Inevitably there is a new housing development under construction nearby.

The windiest locations are along the Marmara Sea, the Meditarranean Coast, the Agean Sea and the vast inland stretches of Anatolia.

Turkey's first windpower plant started spinning in 1998 and churns out 1.5 MW per year. Another 600 MW of windplants are planned to meet the country's goal is to produce 2% of its electric power from the wind. The EU has collectively committed to generate as much as 22 percent of its electricity from renewables by 2010. Poland is the region's wind-energy leader with 68 MW on line.

Turkey's other Renewables

Turkey's 8,210 kilometers of coast also offer a potential wave-energy bonanza of 18.5 TWh/year. Tapping just a portion of one-fifth of the coast could generate 140 billion kWh, which is more than Turkey's annual production of electricity in 2000.

Ninety-one percent of Turkey's energy in produced by TEAS, a publicly owned power company. Although Turkey has one signed the Kyoto Protocol on Greenhouse Gas reduction, it has been rehabilitating its fossil-fuel burning power stations since 1987 and is working hard to cut distribution losses, which currently run as high as 30%.

Under the Electricity Market Law passed in 2001, TEAS is to be broken into three separate units and trade and generation of power will be privatized under the "free market" banner. Germany's Siemens, one of the first companies to respond to the free-market lure, is builidng a $1.45 billion, 1,300MW coal-fired plant near Iskenderum.

Geothermal energy projects are receiving support from the Environment Ministry. Geothermal heat pumps are a new and rapidly growing technology. They use 25-50% less electricity than traditional heating and cooling systems, with a corresponding 44-72% reduction in CO2 emissions. Turkey, which boasts a number of "city based geothermal district heating systems," now ranks among the world's top five countries in the use of geothermal heat.

A Nuclear Turkey?

The military government that ruled Turkey in the 1980s mapped out the first plans for the nuclearization of Turkey and the countries

Turkey's first nuclear powerplant -- a $4 billion, 1300MW nuclear plant backed by AECL (Canada), NPI (France and Germany) and Westinghour-Mitsubishi (USA) -- was supposed to have been built on the Mediterranean at Akkuyu, 15 miles from a major earthquake fault.

But Environmentalists and local residents rallied against the project, claiming that improved efficiencies would obviate the need for the nuclear plant. In July 2000, Turkey canceled the project, citing "financial" reasons.

Turkey's Environmental Crusaders

In 2005, the country's Environment Ministry recognized REC Turkey, as a "national focal point" for Turkish environmental education and action. REC Turkey is part of the Regional Environmental Center (REC) for Central and Eastern Europe, which is based in Hungary and publishes a highly informative English-language quarterly called Green Horizon. In 2007, REC Turkey published the tenth edition of it's own magazine, Yesil Ufuklar.

REC's Turkish office opened on May 27, 2004. On July 13, 2007, a week before the General Election, REC Turkey issued a press release that read: "No need to await new droughts and disasters! For the sustainable future of Turkey and the world, the priority of the Turkish Grand Assembly should be climate change."

While Turkey still hasn't signed the Kyoto Protocol, REC Turkey -- in advance of a July 2007 visit to Istanbul by former US Vice President Al Gore -- gathered 150,000 pro-Protocol signatures in less than six weeks.

As Green Horizons editor Pavel Antonov notes: "Given the amount of nature there is to protect, and the variety of threats it faces, [Turkey's] civil society movement has a lot of work to do."

For more information contact: