A Tourist's Impressions of Turkey

By Gar Smith / The-Edge.org

December 22, 2007

|

| Istanbul's skyline is an intricate mosaic of ancient architectures -- spires, towers and glistening domes -- framed between bright skies and blue water. Credit: Photos by Gar Smith |

If you want to experience the contrasts between a well-run, civilized country and a badly managed, cash-strapped, Third World republic, just hop a flight from the US to Turkey. Unfortunately it's George Bush's America that comes off looking like a banana republic while Turkey strikes a traveler as prosperous, generous and vital.

Flying out of San Francisco on American Airlines, passengers were treated like little more than sentient baggage. AA's "complimentary" banquet consisted of two tiny biscuits. A cheap in-flight lunch included a two-dollar Coke and a five-buck turkey sandwich. "Exact change please," a stewardess scolded as attendants shoved pushcarts down the aisles like stratospheric street vendors, pausing to present bags of oily, salted, sugar-filled fast-food snacks for approval.

In Chicago, we transferred to Turkish Airways (Turke Hava Yollari) and immediately felt like we'd entered the Promised Land. Earphones were presented without charge -- along with gift bags containing eyeshades, lotions, a toothbrush and a pair of sky-blue socks. We were invited to keep the earphones for use aboard future flights.

Meals (chicken/beef/fish/vegetarian) were free and abundant A sample meal included pasta, a salmon dish, Tillamok and Monterrey Jack, sourdough mini-buns, salad with olive oil-and-lemon dressing and side dishes of chopped tomatoes and cucumbers topped off with desserts of chocolate pudding and flan. Coffee and juice refills were endless. Mixed alcoholic drinks were on the house -- for the entire 11-hour flight.

Leafing through a book by the popular Turkish author Orhan Pamuk (charged with "un-Turkish behavior" after citing the Armenian Genocide in one of his works), I read the American translator's comments that the Turkish language is "passive and agglutative" and has no words for "to be" or "to have." If true, that would mean a Turkish speaker could never say, "I am sad" or "I must have that." If language dictates society, you might expect Turks to be neither narcissistic, nor materialistic. That, we would discover, is certainly not the case. Turks are proudly self-referential and ambitiously eager to make a buck.

Welcome to Istanbul

|

| A waterpark south of Ankara glistens in the setting sun. |

Turkey extends from the rainy Black Sea forests of the mountainous Northeast to the verdant horizon-to-horizon fields of central Anatolia to sun-splashed resorts along the southern coast. With a population of 75 million, Turkey is home to Europe's youngest population.

Istanbul lies in Trace, the Western section of Turkey on the European side of the Dardanelles. All but three percent of the country's 779,452 square kilometers lies east of the Bosphorus, in Asian Turkey. The country sits atop three active earthquake faults. A 1999 quake in Ismir and Adapazari killed 18,000. It is only a matter of time, seismologists predict, before a large quake strikes Istanbul. When that happens, much of the city -- and its incredible collection of ancient treasures -- will be destroyed.

The climate was big news everywhere in Europe. Scorching temperatures baked much of Europe as gigantic fires broke out in Greece and Spain. In Bulgaria, 1,800 blazes erupted in a single week. Thermometers across the region were bubbling at 46°C (115°F). Some 500 people reportedly died from heatstroke in Romania while torrential rains left much of Britain submerged in epic floods.

"It snowed in eastern Turkey two days ago," our tour guide notes. "This is very unusual." Every time the topic of the weather comes up anywhere in Europe, someone invariably utters the phrase "climate change."

On the streets of Istanbul, a smiling Gypsy girl of about seven jumps into our path holding a wooden top. She quickly wraps it in string and sets it spinning on the sidewalk. Then, with surprising agility, she catches the top with the loose line held between her hands and flings it into the air. She leans backwards and the top falls to her chest, just below her chin, still spinning. "Do we want to buy one," her dancing eyes ask? It's hard to refuse.

Shuffling towards the Sultanamet, we are chased down by a young Turkish gentleman named Chance.

"Hold your horses!" he exclaims, followed by the soon-to-be-familiar phrase: "Where are you from?"

In the ensuing conversation, we learn about Chance's cousin in Los Angeles. We learn that Al Gore is such a "Sopranos" fan that, when he visited Istanbul a few weeks earlier, he boasted that the producers had given him a bootlegged copy of the final episode, just so he wouldn't miss it.

Naturally, Chance has an ulterior motive. He has a carpet shop "across the street" and he invites us to visit. Three blocks later, we come to a building covered with shining shards of pottery. Inside, we're offered glasses of hot apple tea and invited to peruse carpet collections on the second floor (modern) and third floor (antiques). Chance hands us over to Bulim, a tall, elegant, blond gentleman who spends six months each year driving across the US selling and exchanging Turkish carpets -- keeping alive the spirit of the Silk Road.

Merchants dominate Istanbul's streets and each has an opening line (in English, French, German, Spanish, and Russian). They range from the ordinary -- "Hello, hello!" "No problem!" "Where are you from?" -- to the inspired -- "Excuse me: May I tell you the story of my life?" and "Hello, my name is Burhan. How may I help you spend your money?"

Ankara and Atatürk

"After WW II, Europeans seized sections of Turkey," our guide relates. "Only Ankara and parts of the Black Sea were left to the Turks." And so the situation remained until Mustufa Kemel Atatürk "lit the fire of Independence."

In Ankara, we pause to visit Atatürk's mausoleum, the Anit Kabir. The core of this massive Parthenon contains soil from every town and village in Turkey. Every October 29 Independence Day, millions flock to the site to pay homage to the founder of modern Turkey. And they return again, two weeks later, to honor Atatürk's birthday on November 10. **

"Atatürk was the greatest visionary of the 20th century," our guide informs. "Women were given the right to vote in Turkey before Britain. Tunisia and India followed Turkey's struggle for independence." Atatürk explained that his goal was not "Westernization" but "civilization." His motto was: "Peace at home; Peace on Earth." One measure of Atatürk's long-view was his insistence that the main street in the new capital of Ankara should be 100 meters wide -- wider than any other existing concourse in Europe. Some 80 years later, the boulevard is jammed with traffic.

But even the Turks will admit that while their beloved Atatürk "defeated armies, he could not survive marriage." After two years of marriage, Atatürk "surrendered" to his first and only wife and got a divorce. He called his wife his only successful opponent. Zsa Zsa Gabor was one of Atatürk's great loves. It was she who convinced her husband, Nicky Hilton, to build the hotel chain's first foreign operation in Turkey.

Leaving the capital, we head into the countryside to spend a night at the massive Büyük Anadolu Hotel, which rises incongruously from a vast plain of crops and small villages. Rising alongside the hotel, equally incongruous, is a large soccer stadium, an equestrian stable, and a sprawling water park.

Waterparks are springing up all over Turkey. They may even outnumber the caravanserai that line the old Silk Road. The caravanserai provided free lodging to traveling merchants and traders (in exchange for a toll collected at the border). They were built at regular intervals -- "the distance a camel can walk in a day." These fortress-like motels featured just one door that opened at dawn and closed at dusk. (And how many miles can a camel walk in a day, you ask? About 20 km, with stops.)

The Büyuk's charming Hotel Rehberi greets English-speaking visitors with the following written invitation: "Our first priority is to provide you to get the best comfortable and the best merry instandtds. If you are not satisfied with any part of your stay that we are not wishing you to get any. Please bring it to our attention for our best service in the next."

|

| I felt like Istanbul had decided to throw a party in my honor when I saw these brochures. It turns out that "gar" is Turkish for "station" or "terminal." Nightly bellydancing shows are held in a building at the foot of one of Istanbul's main roads. |

Kicking back in Antalya

The seaside resort of Antalya boasts a wide, curving beach that's called "the Riviera of Turkey." Before breakfast, we trot down a quarter-mile switchback to the beach and plunge into the Mediterranean along with other early-morning bathers. The beach is covered by stones the size of jelly beans. Young Turkish boys frolic in the shallow surf, grabbing stones from below the water to fling at one another.

At the top of the hill leading to the beach, a tram takes visitors to the Old City. After a 30-minute wait in wilting 90-plus-degree heat, we clamber aboard for a 17-minute ride to Hadrian's Gate, the entrance of the Old City. We climb to the top of the massive Roman-built gate and, on our way down, encounter two fellows lounging around a small table in the small plaza, sipping tea and making eyes at the passing ladies. "I looooove yoooo!" the older man grins over his shoulder as a smiling American woman strides by.

After chatting with them for a minute, we discover that we are in the presence of a true national celebrity.

"He is the current Oil Wrestling Champion of Turkey!" says the older man, pointing at his younger companion. "And," his friend responds, "he is the former Oil Wrestling Champion of Turkey!"

Despite the fierce nature of this national competition, the two muscular athletes are fast friends. The older wrestler invites us into his tourist shop nearby where, sure enough, there are photos of both men in competition, raising their arms in victory.

On the Road to Cappadocia

The bus rumbles through wheatfields and rows of sunflowers. We pass biodiesel stations and Topaz LNG filling stations. There is a lot of market diversity. In addition to the numerous Shell and BP stations, there are hundreds of way-stations owned by Petrol Ofisi, Akpet, Sunpet, Upet, Alpet, Termo, 1 Gaz, Niggaz, Sungas, Güneygaz and Erk.

At a caravanserai that's still standing along the old Silk Road, a vendor asks where my companion is from. Her reply, "the West Indies," elicits a blank stare. "Near Venezuela?" she offers. Nothing. "Cuba?" Suddenly the vendor is animated. "Yes! Cuba! Castro! Workers!" He is suddenly pumping her hand, grinning broadly and laughing. "Friends! No America! Shake hand! America enemy!"

The night before arriving at Capadocia, I'm hit with food poisoning. After spending the night exploding from both ends, I'm weak and dangerously dehydrated. I can walk, but only with difficulty. I need to replenish my electrolytes but Gatorade is hard to come by. At a view stop along the road, I creep from the bus and totter up a sandy slope toward a vendors stall in hopes of scoring a sports drink. The bearded gentleman behind the counter raises empty hands when I make my request.

"My friend, what is your problem?" he asks. When I explain, he reaches below the counter. With a smile, he pulls out a small brown bottle and pours a jigger of thick, pale liquid into a cup.

"Drink!" he commands. I bolt the brew and it sends my throat and tongue ablaze. I feel like I've swallowed molten lead but, just as suddenly, I feel an amazing blast of energy. My head clears and my strength returns.

"What was that?" I ask.

"I am Hawan," my savior relies. "It is strawberry vinegar with a ton of flowers."

When I offer to pay him, he refuses. "It is for your health," he remonstrates.

"Can I buy something else from you?" I ask. "Only if you wish," he replies.

I purchase a bottle of mineral water and sprint back to the bus, clicking my heels at the door and yelling, "I'm cured!"

|

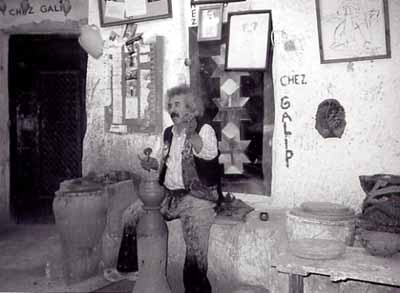

| Despite the encroachments of modernity, Turkey still glories in many ancient crafts traditions -- carpet-making, goldsmithing, farming and pottery. |

Housing the Masses

Across Turkey, massive housing developments are rising on hillsides surrounding major cities. Some were built following the devastating 7.9 quake that demolished Izmir in 1999; others are being built to accommodate tens of thousands of refugees fleeing political strife in neighboring countries. The 1990s saw 100,000 refugees from Bosnia.

On Istanbul's hilly outskirts, new highrises are rising to replace shantytowns that have sprung up on the flanks of the sprawling megalopolis. Some hills northeast of Istanbul are still encrusted with squatter settlements -- urban encampments of stone, wood and cement with hand-built roads accommodating brand-new automobiles. But by now, most of these settlements have been removed -- leaving behind poignant patterns of rubble strewn down the mountainsides where state bulldozers pried the homes from their moorings. Today, alongside each cleared stretch of hillside, modern eight-story apartments are rising by the hundreds.

"How many years has this housing development been underway?" we ask our guide, marveling at the scale of the construction work. "This is all in the past year," he says.

The scale of Turkish urban renewal drawfs anything the US has been able to accomplish. The frenzy of new construction beggars belief. These new towers sprout open-air balconies, distinctive tiles and design elements, and the multi-colored, vertical paint schemes found on many older buildings. The vertical bands of pastel make the apartments resemble colorful carpets hung out for display on the slopes.

One could say that these new highrises not only carpet the hillsides, they also loom on the horizon.

For more information contact: