The International Criminal Court: How Bush Courts Disaster

July 19, 2002

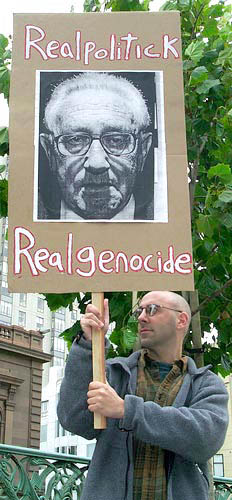

Henry Kissinger now admits that that mistakes were made in Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, Indonesia and Chile. But even if he is guilty of war crimes, he is beyond the reach of the new International Criminal Court. Photo credit: David Hanks/Global Exchange. |

George W. Bush's latest nullification of a major treaty came in May, with a one-paragraph letter to UN Secretary General Kofi Annan scratching the signature of former President Bill Clinton from the treaty establishing the International Criminal Court. The ICC treaty had been signed by 139 other countries and ratified by 67.

On July 1, 2002, the ICC officially came into existence - without US participation. It is expected to be ready to hear cases by July 2002.

Annulling the ICC treaty followed the US black-balling of the Kyoto global warming treaty, the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty, the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, the Biological and Chemical Weapons Treaty, the Land Mine Treaty and the Small Arms Treaty.

The one treaty that Bush did sign, a three-page nuclear warhead reduction agreement signed with Russia, is not all that the White House wants us to believe. Under this treaty, nuclear warheads are not to be junked, they just go into storage and the 10-year treaty allows either side to cancel the agreement on 90 days notice.

[Note: Under this treaty, the warheads need only be "withdrawn" for a single day - December 31, 2012 - the day before the treaty expires. For more information see: www.nrdc.org/media/pressreleases/020520.asp]

Joe W. Pitts, a Dallas-based businessman and an international lawyer, has represented nongovernmental organizations at UN and NATO conferences. Speaking on National Public Radio recently, Pitts suggested that Bushs withdrawal from the ICC was akin to seeing all your neighbors fighting a horrible fire; but the richest neighbor not only stays home and not only turns off his spigot so others cant use his water, he sets fire to his own house.

In the following essay, Pitts ponders the implications of Bush's action and offers a realistic assessment of the scope of the ICC.

Why the ICC Does Not Threaten US Sovereignty

By Joe W. Pitts

Genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity killed well over 100 million civilians in the last century. By unsigning the ICC treaty on May 6, the US took another step away from the world at a time when it needs the worlds support more than ever.

Unsigning this treaty is unprecedented and could cause serious problems with the integrity of international law in general. Whats to stop other nations from unilaterally unsigning other treaties - including the 12 anti-terrorism treaties that cover hijacking, kidnapping and the financing of international terror?

Like the existing International Court of Justice (the World Court) that deals with disputes between governments, the ICC will not deal with intergovernmental disputes, only with cases against individuals. The ICC will step in only as a last resort in the event that no national court with jurisdiction is able or willing to try a case.

In the future, perpetrators of atrocities, including heads of state like Pol Pot and Slobodan Milosevic will be newly accountable before a permanent tribunal of 18 judges. Perpetrators of war crimes will be deterred by a new environment reducing the impunity that prevailed before.

Opposition to the ICC stems from the fear that it steals US sovereignty. Critics in the US contend that our leaders, diplomats and soldiers, doing the good work of peacekeeping or humanitarian intervention overseas, will be hauled before this unelected and unaccountable court.

Any treaty affects US sovereignty to some extent. Existing international law already subjects Americans to trial abroad in many instances, including for crimes on foreign territory and for violating treaties on drugs, hijacking or terrorism.

Lead by conservative Representative Tom DeLay (R-TX), who called the ICC a rogue court, the GOP-controlled House Appropriations Committee voted to authorize the president to use military force to rescue any American brought before the ICC in The Hague. The American Servicemembers' Protection Act (which has been called The Hauge Invasion Act) would also bar sending US arms to all nations that ratify the ICC treaty.

Overreacting Reactionaries

If the US had accepted the ICC treaty, it could still have insulated its citizens to a significant extent simply by initiating its own good faith investigations and, if warranted, prosecutions in US civilian or military courts. Only if the resulting local proceedings were a sham - unlikely in a judicial system as widely respected as ours - would the ICC be able to step in.

For a nation increasingly acting as the worlds policeman, there is undoubtedly greater exposure to accusations of war crimes. But is it really a threat to US national interests to have its power at least partially checked by global norms? They remind military planners not to target civilians and to minimize collateral damage, thus limiting backlash and enhancing overall security.

The ICC can only consider the three most serious crimes: genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity. The less well-defined crime of aggression could only be added by a treaty amendment and amendments cannot be considered for seven years.

A crime against humanity must be the result of a knowing policy of systematic attack on a civilian population. Attacks such as those of Al Qaeda on September 11 would meet this standard. A single, isolated murder would not. Only crimes committed after July 1, 2002 will be subject to the treaty.

Other protections are procedural. The ICC prosecutor can only refer cases for investigation after presenting the evidence to, and getting the approval of, a three-judge pre-trial panel. A similar process is required for an ICC indictment.

Any individuals accused, and the nations concerned, have an opportunity to have advance notice of an ICC action and the right to respond and object. All the rights granted to criminal defendants under the US Constitution apply at the ICC, except the right to trial by jury, whcih is not the norm outside the US and former British Commonwealth.

The UN Security Council, in which the US wields special powers as a permanent member, can defer ICC action indefinitely. The ICCs legitimacy, budget, power, effectiveness and even continued existence will depend on its reputation, especially with the major powers on the Security Council.

If the US, or any nation, fails to prosecute a likely perpetrator of an atrocity, it is essential for the cause of justice to allow the ICC to step in. The Bush administration says that if a genocidal murderer is discovered on US soil, the US will not extradite the person to the ICC. No nations nationals are entitled to be totally shielded from prosecution for such a crime.

[Note: The administrations position could have the effect of turning the US into an international sanctuary for fugitive war criminals - The-Edge].

Standing Alone

This attitude of US exceptionalism is a major source of the significant anti-Americanism in the world today, and of the terrorist manifestations of anti-Americanism.

The 40-plus nations of the Concert of Europe find our position ludicrous and appalling. The administrations actions reveal a deep antipathy to international law, international institutions and multilateralism. The US finds itself virtually alone against the rest of the world in its position on global treaties.

In rejecting the Convention on the Rights of the Child, the US had the company only of Somalia. (That is, until early May, when Somalia signed the treaty.) When it comes to recognizing the rights of children, the US now stands as the lone holdout in the world.

The ICC epitomizes a framework of the rule of law, as opposed to the anarchy preferred by terrorists. Had the ICC existed on 9/11, it would have offered a useful international alternative for trying terrorists. It would have mobilized global anti-terrorist sentiment and limited the clash of civilizations that is the Al-Qaeda agenda.

US opposition to the ICC undermines the rule of law, offends our allies and the rest of the world, and undercuts the coalition against terror that was emerging. It weakens a tool against terrorism and for a global culture of peace and justice. It places the US on the wrong side of history, as well as of our own national interest.

Ben A. Franklin is the editor of The Washington Spectator [London Terrace Station, PO Box 20065, New York, NY 10011, Annual subscriptions: $15 for 22 issues]. This is an edited version of a longer analysis that originally appeared in the June 1, 2002 issue of the Spectator.

For More Information Contact:- Washington Working Group on the International Criminal Court, c/o World Federalist Association [418-420 7th Street, SE, Washington, DC 20010, (202) 546-3950, fax: (202) 546-3749, www.wfa.org/issues/wicc]

- The Rome Statue of the ICC [www.un.org/law/icc]

- Coalition for the ICC [www.iccnow.org].

Elie Wiesel on the American Servicemembers Protection Act

Fifty years ago, the United States led the world in the prosecution of Nazi leaders for the atrocities of World War II. The triumph of Nuremburg was not only that individuals were held accountable for their crimes, but that they were tried in a court of law supported by the community of nations.

[The ASPA] would erase this legacy of US leadership by ensuring that the US will never again join the community of nations to hold accountable those who commit war crimes and genocide. A vote for this legislation would signal US acceptance of impunity for the World's worst atrocities.

America's Allies in the War against the Rule of Law

Most of the world's nations have signed (and remained signatories to) the Rome Statute establishing the International Criminal Court. George W. Bush's revocation of President Clinton's signature now puts the US in the company of other ICC hold-outs including North Korea, Iraq, (two of the "Axis of Evil" countries), Rwanda, Somalia, Pakistan and Afghanistan.

Other countries that had failed to endorse the ICC as of July 2002 include: Azerbaijan, Belarus, Bhutan, Brunei, China, Cook Islands, Cuba, El Salvador, Equatorial Guinea, Ethiopia, Guatemala, India, Indonesia, Japan (which reportedly intends to sign), Kazakhstan, Kiribati, the Laos Peoples Democratic Republic, Lebanon, Malaysia, Maldives, Mauritania, Micronesia, Nepal, Nicaragua, Palau, Papua New Guinea, Qatar, Russia, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, Sri Lanka, Swaziland, Togo, Tonga, Tunisia, Turkey, Turkmenistan, Tuvalu, Vanuatu and Vietnam.

For more information contact:

ICC Print and Electronic Resources [www.lib.uchicago.edu/~llou/icc.html